It wasn’t supposed to be this way. Rome was supposed to be a republic, not a kingdom: “There once was a dream that was Rome…”1 And cars were supposed to be built to order, not to stock. After over a century of “Pile ‘em high and sell ‘em cheap!” the Covid shock and chip shortage were supposed to have to taught us this lesson: don’t pile ‘em up (keep production below demand, and thus inventories low) and sell ‘em dear (because demand would always exceed supply, and low inventories would relieve the urge to discount).

And for a while it worked. Temporary chip restraints on supply and temporary pandemic boosts to demand2 held sales volumes low and kept sales prices high, and inventories at dealerships evaporated. The OEMs made good profits and so did the dealers. But today both the restraints and the boosts are gone, OEM and dealer profits are normalizing, and inventories are building again. (You can see charts on all these variables everywhere online, so I won’t inflict them on you here.) Even Tesla, which for years was “supply limited” (there was an immediate buyer for every car they made) is now “demand limited” (with a third or more of its revenue generated by cars in inventory - that is, cars which were built with no pre-arranged buyer lined up).

Again, there had been high hopes that it would be different this time. That somehow “the OEMs”3 would “exercise discipline” and hold production down, and thus sales down, and thus prices up, and inventories down, and happy days would persist.

The problem with this hope is that it relies on some sort of vague belief in the concept of “discipline.” Discipline is not really the problem in my view: every OEM executive understands what happens when supply exceeds demand, so it’s not a matter of weak moral fiber when he or she decides to turn up the production rate. It’s a matter of economics, specifically the economics of breakeven points.

Apologies: herewith a Microeconomics 101 lecture. Profit breakeven occurs when sales volume is sufficiently high that revenue covers both fixed costs (e.g., rent, utilities, insurance) and variable costs (e.g. wages, raw materials). Above that level of unit sales (and dollar revenue), fixed costs are fully covered and the product starts to make money; below that point there is only loss, not profit4. Thus management is highly focused on getting production (and sales) above breakeven.

The problem is that the auto industry is a high-breakeven-point industry, meaning that the urge to produce is very strong. In fact, I’ll assert that for the industry as a whole profits don’t emerge until capacity is 80% or even 90% utilized, because our fixed costs are so high. Assembly plants cost billions to build, suppliers of components cannot be easily turned on and off, R&D budgets dedicated to finding cheaper battery technologies or safer autonomy software are enormous, etc.

This high fixed-cost burden is in sharp distinction to, say, that of a real estate agency. The agency may have no assets other than a small office and a few computers and phones. When demand for houses is high, the firm hires more agents to get houses sold and profits will soar. When demand is low, profits are still possible, since we just lay off all our agents and cover our minimal fixed costs with an occasional sale. A real estate agency may thus have a break-even point as low as 25% of target “capacity” (itself a little tricky to calculate when your production equipment is mostly people!)

The obvious problem with enormous pressure to produce and sell is that it kills profitability. As cars keep coming off the factory line faster than Lucy and Ethel can wrap the chocolates (showing my age here), the urge to cut price becomes overwhelming and factories and dealers alike slide into lower profits or even losses. We have seen this at the publicly-traded dealers such as Lithia and AutoNation, whose new-car profits are rapidly regressing back to the mean of 2019 or earlier.

All of this (sorry!) is by way of introduction to our Car Chart today, which attempts to reveal exactly what our breakeven point is. Because, believe it or not, this number is incredibly elusive. Accepted wisdom is “8o or 90 percent, I guess,” but try finding any hard numbers behind that! We have a few places we can look, such as:

OEM income statements, where we can back into break-even from gross margins, but this is extremely rough and lumps together all sorts of complicating factors (e.g., over time and geography)

Assembly plant economics might give a clue, if we look at the split between capital and labor costs, but this number is incomplete, since the cost of building the car is actually a small portion of total cost.

But I like to rely on what I think is the Holy Grail of automotive breakeven, which comes from the Original Equipment Supplier division of MEMA (the Motor & Equipment Manufacturers Association), provided in their periodic Supplier Barometer studies.

This is because if anyone knows breakeven, it is an automotive component supplier. Dealers can make money on new cars through both price and volume, OEMs similarly, but - to simplify to a ludicrous degree - over any short run of time suppliers make money on volume only5. This is because widget prices do not flex up and down with demand from week to week or month to month or in some cases even year to year. The supplier “makes or breaks” on unit volume.

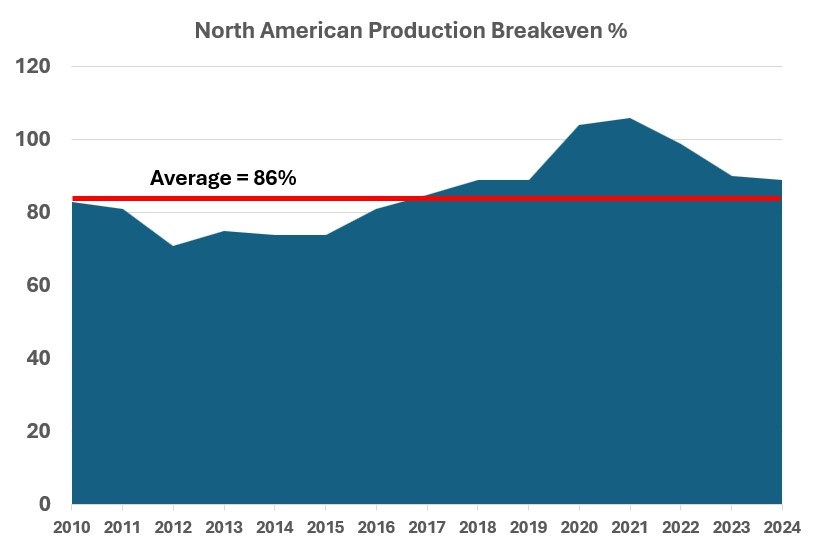

I took various back issues of the Barometer to extract breakeven levels back over time, in order to look for a long-term pattern. And here it is:

Source: OESA/MEMA, various years6.

In each Barometer a very large sample of North American OEM automotive suppliers are asked to do this: “Considering North American light duty vehicle production, estimate the required industry volume needed to achieve breakeven in your North American operations.”

And the answer is 86%, which in this case actually well supports Accepted Wisdom! Further, supplier breakeven is a good proxy for OEM breakeven, since purchased components make up roughly 75% of the cost of producing a car, on average across OEMs. (Why is supplier breakeven so high? Capital (fixed cost) intensity: lots of expensive machines and molds and dies and tools, which cost almost the same whether the line is running or not.)

So there you have it. If the supplier and OEM breakeven point is 85% of capacity, even the slightest pullback in customer demand will cause panic in the executives suite, triggering discounts (“if we cut price they’ll buy more”) and inventory builds (“if we give them more choices they’ll be sure to find something they like”), financing subvention (“just pretend the residual value is higher, that will bring the lease payment down”), and other bad behaviors.

There are many reasons why the global (new-car) auto industry, with special cases like Ferrari excepted, struggles to make good profits, or even cover its cost of capital. (I could go on…. but that’s for another post.) But a central, maybe the central reason, is that our breakeven point is so high. Customer demand will fluctuate, from day to day and week to week, from hot Model A to cold Model B, from blue cars to red cars, from high to low price and back again…. but back at the factory, every 60 seconds or so another unit pops out, and the line just does not stop7.

I hope you do not need a citation for that line!

“Starting in March 2020, the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES Act) provided Economic Impact Payments of up to $1,200 per adult for eligible individuals and $500 per qualifying child under age 17. The payments were reduced for individuals with adjusted gross income (AGI) greater than $75,000 ($150,000 for married couples filing a joint return). For a family of four, these Economic Impact Payments provided up to $3,400 of direct financial relief.” (Dept. of the Treasury)

A pretty meaningless term, given how heterogeneous OEMs are: the phrase has as little coherency as “the Americans” or “the Millennials.”

Note that even below breakeven it often makes sense to continue operating, since each additional unit of revenue will typically cover all variable costs and contribute something to fixed costs.

Partly as a result of this, suppliers have not participated in the profit upsurge the OEMs and dealers have enjoyed. As Roland Berger notes in their latest “Global Automotive Supplier Study” (2023), “Compared with pre-crisis levels, the automotive supplier industry has structurally lost three percentage points on EBIT margin,” though the reasons for this are more complex than just volume issues.

You can see how during the demand collapse within the pandemic years breakeven went above 100%, meaning that even with reductions in capacity, demand was so low that plants would still lose money even if running flat out.

In fact, the in the specific case of the paint line in a vehicle assembly there is almost no stopping ever, as it is so costly to shut down and restart this gigantic beast, which operates almost as one single huge machine. The champs of uptime, however, are float glass lines (which make glass for various applications, not just automotive), which can run 24/7 for several years at a time.