(All the charts and data in this post are from the recent Bernstein research note “Chinese Autos: Huawei's EV ambitions and capabilities; Who are the winners and losers?” Lead author Eunice Lee very graciously has allowed me to excerpt from that excellent report, which I encourage you all to read. Thank you, Ms. Lee. Any misinterpretations of her findings are of course my fault.)

My additional thanks go to Apple for giving me this post’s title: I was going to write up Huawei anyway, but the announcement of Apple’s pulling out of its multi-year car project provides a nice compare-and-contrast moment.

I often carp that there is very little new under the automotive sun. For example, we’ve been standardized on the classic four-step (stamp/weld/paint/assemble) integrated car plant for many decades. Various challenges to this system have emerged over the years (e.g. modular assembly, localized “microplants,” paint-in-die, etc.) but it persists. And speaking of the number four, save for the immortal Reliant Robin,1 we’ve been standardized on four wheels for cars for a similar stretch.

But there may be something new coming from China, in the form of Huawei’s entry to the auto industry. Traditionally, a car company (OEM) designs and assembles the vehicle, buying in parts and systems from a tiered array of suppliers. There are various options for how this is actually carried out: some OEMs offload a great amount of design responsibility to suppliers, others less; some OEMs contract out parts of final assembly (often for specialized low-volume variants such as convertibles), others do not. And increasingly, suppliers are delivering software as much as hardware, both B2B applications and B2C products such as Android Auto and Apple CarPlay. But in the end the car is identified with the OEM’s brand: the Porsche is a Porsche even if many of its parts are from Bosch or Magna.

Huawei may be changing this paradigm, as Lee’s note points out, though I am extrapolating the implications more aggressively than she is, probably to my peril2. While Apple has retreated from producing a car, Huawei is moving into car production, but in a novel way. To quote the Bernstein note (emphasis added, lightly edited for concision):

Huawei isn’t directly involved in EV manufacturing, but acts as a supplier to the industry. … Although Huawei technically does not manufacture cars themselves, under the HIMA partnership, it collaborates deeply with some OEMs … and jointly develops EVs … , which are commonly referred to as “Huawei cars” by the public. Huawei’s ambition is to help its OEM partners reach 1 million units of annual sales by 2025. In other words, Huawei is aiming for a 9-10% EV market share, or a 5% overall share [ based on our forecasts for EV sales volumes ]. Huawei expects that with the scale of 1mn units, the automotive BU will be able to reach profit breakeven.

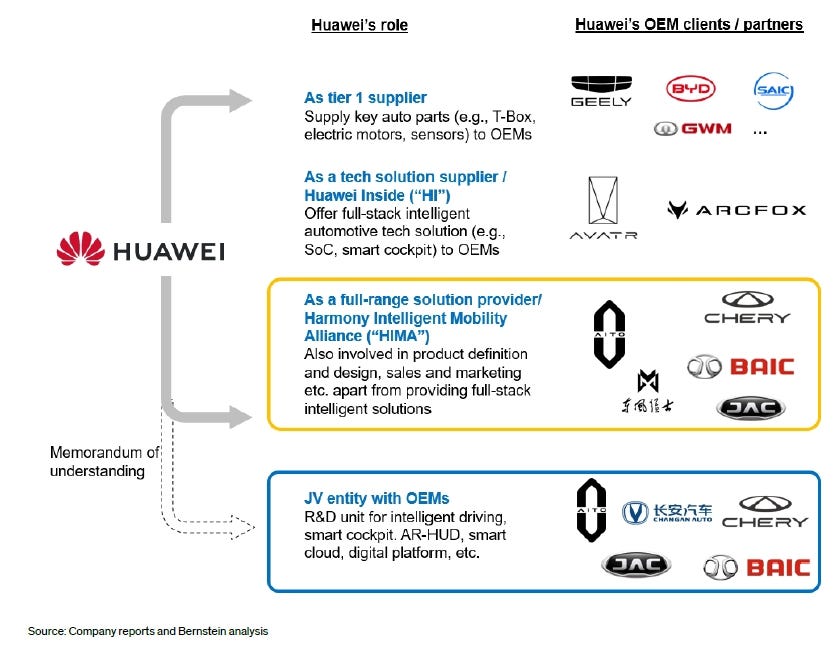

Huawei acts as an OEM supplier in the “normal” ways, as shown in the two upper branches of the chart below:

As a Tier 1 supplier it acts like a Bosch, supplying parts and enabling software. As a Tech Solution Supplier it acts like an Apple or Google, supplying CarPlay and Android Auto. But in the lower two branches it goes much further.

As the HIMA supplier it is deeply embedded in the entire value chain of the OEMs it is working with, even into marketing and retailing, for example marketing AITO brand cars via its 1,000+ Huawei phone stores and its 50+ specialist HIMA stores (a number which it plans to expand to 800 [ sic ] by the end of 2024). This would be like Apple promoting cars from its own iPhone and iPad stores, plus a new set of stores to sell the… iCar.

Then finally, Huawei intends to set up full-fledged JVs with OEMs to further embed itself in the development and sale of cars.

I believe this expansion into the automotive business system is transformative and novel, in two ways, one of depth and one of breadth.

The depth of involvement is shown in the above chart: Huawei does not stop at delivering products to OEMs, but works with and around them in marketing and retailing cars as well (to the point where customers refer to these as “Huawei cars,” even though they are not built by Huawei).3

The breadth is also visible from that chart: Huawei is working openly with a wide range of OEMs, who are all competing with each other. This is an indirect tribute to the power of Huawei’s brand in China, in that OEMs are willing to swallow their pride and essentially co-brand with Huawei. (The next chart shows the strength of the Huawei brand.)

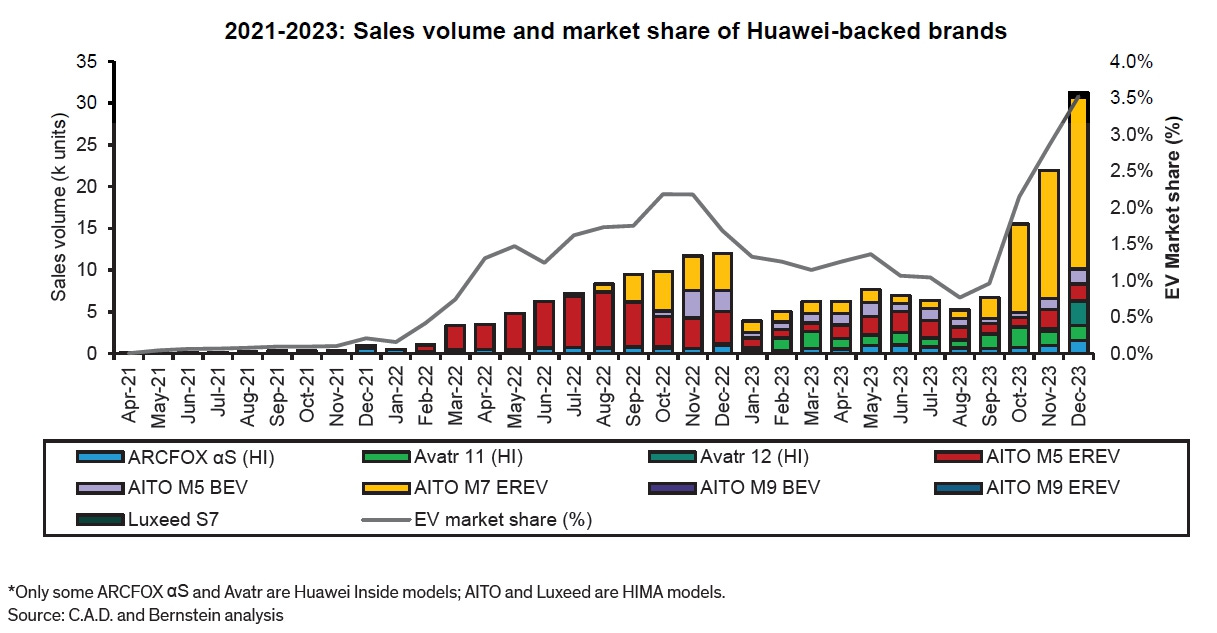

How is it going so far? Not bad, IMHO4:

What are the implications of this move, wherein a firm from outside the industry moves in, and in the space of a couple of years or so, through broad and deep participation, on the producer side signs supply or JV deals with some ten OEMs, and on the customer side effectively establishes itself as a viable (co) brand? This is “Intel Inside” taken to a new level.

If it works, we may be facing a new way to compete in automotive, one given its genesis when years ago someone first called a car “a smartphone on wheels,” wherein a smartphone company can sit at the same table with its OEM customers, and do so in full view of the public. Surely a redistribution of profit pools would follow.

But will it work? There are more than a few roadblocks that Huawei will have to navigate:

First, with the political controversy raging around the company, it is unclear how much of this model can be implemented outside China.

Next, will OEM customers tolerate Huawei’s growth over time? If I am an OEM with a weak brand, linking up with Huawei might help - but at some point don’t I want to go it alone?

There is the issue of liability. In the traditional industry all product liability starts with the OEM of record. If there is a product failure, perhaps resulting in death or injury, the litigation starts there, and then works its way through the supply chain, depending on individual responsibilities and contract terms. It is often a messy process, and has gotten more so recently: see for example debates as to how accident liability may shift from driver to the OEM when a car is in autonomous mode. But certainly the emergence of a “super supplier” like Huawei will complicate this further, as courts and regulators try to decide whom is responsible for what.

And finally, there is the matter of execution: this is an incredibly resource-intensive strategy, and success will depend on the number and skill level of the engineers Huawei throws at it. However, Huawei got where it is by outcompeting a few hundred rivals over time, so its abilities cannot be discounted.

I don’t know if Huawei can overcome these or other issues that will crop up. And maybe, like Tesla in a way, Huawei’s approach may turn out to be an exception rather than a rule (will we see “Denso cars” or “Bosch cars”?). But it is (as far as I know) a novel approach. My November 1, 2023 post discussed how the Chinese might change the basis of automotive competition in terms of products - with this current post I can see how they might change (for some OEMs in some cases) the basis of automotive competition in terms of process.

(And again, read the Bernstein note: for the info it contains, and for a view of Huawei undistorted by my summation.)

Postscript: From a very recent (March 8) Bloomberg article, by Yihui Xie : “Aito, the car brand from Huawei Technologies Co., is China’s best-selling electric vehicle among EV upstarts for a second straight month, a sign how far Chinese smartphone makers have come in their endeavor to take on some of the nation’s brightest automobile hopefuls.”

Calm down, gearheads! I acknowledge also the existence of the Morgan, the Slingshot, the Messerschmitt, the absolutely brilliant Scott Sociable, and all the other 3-wheelers.

For those who need a Huawei refresher, the company is a Chinese multinational that produces telecommunications equipment, consumer electronics, and various technology services. Founded in 1987, it has grown to become one of the world's largest smartphone manufacturers and a leading provider of networking equipment, particularly for 5G networks. Its current revenue is about $100 billion.

We see an echo of this in America, in the case of Cummins, whose diesel engines are clearly co-marketed along with the RAM-branded trucks in which they are installed.

By the way, Bernstein’s commentary on this chart drives home for us just how fast the Chinese move. As the note says (emphasis added): “AITO, which is the Huawei-Seres partnership, has been the only success so far, but it also took a long time to get there. AITO began delivering M5 at the beginning of 2022 and M7 later in the year but sales momentum couldn’t be sustained after initial excitement fizzled out. It was only until the brand launched the M7 facelift and got the pricing strategy right, that the partner-ship seem to show more promise.” Only in China would we consider enduring just a year’s delay in reaching sales targets (2022 to 2023) to be “a long time.”