NOTE: Additional information added post-publication, in footnote 4!

[ It’s been a while, sorry: other matters intruded. I am happy to refund any disappointed readers 100% of their subscription cost, which is…. zero. ]

This post was triggered by the excellent transportation writer and expert David Zipper, whom you really should read if you want a well-informed and well-balanced take on many of the mobility issues that are plaguing us. He mentioned a brand-new study1 that tried to quantify the impact on traffic speed as vehicles grow larger: obviously, a highway carrying nothing but Mini’s will move more vehicles over any period of time than if it were carrying nothing but Class 8 tractor-trailers.

I’ve always been interested in this topic, because it seems obvious to me that this effect exists, yet it is hardly ever mentioned in conversation. We talk about traffic being bad simply as a function of how many cars are on the road, not taking into account what sizes or types of cars they are.

Traffic and road planners of course do take this into account - sort of. Should you be obsessed enough to download the entire Transportation Research’s Board Highway Capacity Manual (7th Edition), all two thousand, four hundred, and forty-three pages of it, you will see that while road capacity planners take into account what percentage of traffic will be very large heavy-duty trucks (like tractor-trailers), nowhere in the manual are different sizes of personal vehicles addressed. Thus planning standards for a road in say, Maine, traveled by nothing except Outbacks, are the same for a road in say, North Dakota, traveled by nothing except Ford F250 dually pickups.

(The term of art involved, by the way, is PCE: passenger car equivalent. Thus a typical tractor-trailer on a flat road might impact road capacity, in terms of traffic flow, as much as 2.5 cars, for a PCE of 2.5. And on steep roads, where these trucks struggle to maintain speed, that number can rise to 4 or 5 or even much more. I think we’ve all been stuck behind slow-moving big rigs, and can understand intuitively how that number works.2)

The Gao & Levinson study showed3 very clearly that as larger vehicles become a greater proportion of the population traveling a given highway, that highway’s capacity falls. The trouble is, their research methodology could not tease apart the impact of more big commercial trucks on the road (like tractor-trailers or Amazon delivery vans) and more big personal vehicles (like pickup trucks or SUVs) relative to sedans or sedan-like crossovers4. And I wanted to know factually if Expeditions and Silverado’s were indeed slowing traffic as much as my perception told me they were.

It turns out this is just not studied much. But I kept digging, and found two good sources.

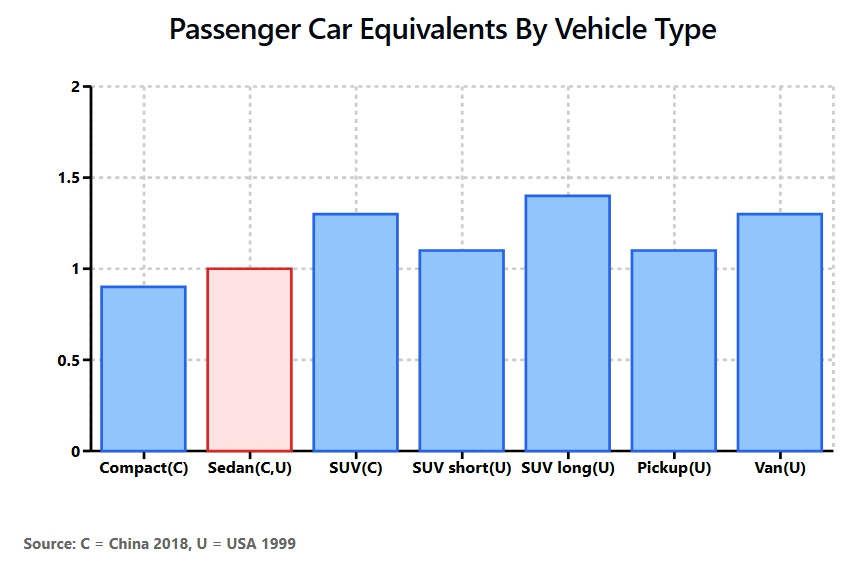

There was a Chinese report, “Measuring the Passenger Car Equivalent of Small Cars and SUVs on Rainy and Sunny Days” (2018, Majid Zahiri1 and Xiqun Chen), which compared compact cars and SUVs and came up with PCEs (relative to 1.0 as a typical passenger car) of 0.9 for compacts and 1.3 for SUVs. This was a relatively new study (2018), but done on foreign roads.

A second study, “Effect of Vehicle Type on the Capcity of Signalized Intersections,” by Shabih and Kockelman, was carried out on American roads and looked specifically at personal vehicles like pickups, but it was done way back in 1999 (when pickups weren’t as large as today). Yet they got roughly similar answers: big SUVs at a 1.4 PCE for example. Close enough for me, but as always see footnote #3. Here’s the chart of combined findings:

All right, what does this all mean for actual traffic flow? There is a rule of thumb one can apply:

Assume base capacity of an American highway is 2,000 vehicles/hour/lane (standard for uninterrupted freeway flow with passenger cars).

Assume by definition baseline PCE is 1.0: nothing on this road but Camrys and Cobalts.

Now replace every vehicle with an SUV, average PCE = 1.4.

New capacity is 2,000 / 1.4 = 1,429 veh/hr/lane,or a a reduction of 28.5% in capacity.

Very simplistically, replacing all the cars with SUVs on this hypothetical road - assuming it was at absolutely full capacity5, “slows down” traffic by 28%. As always, there is more to the real math than this, but you get the point.

So the American love of plus-sized rides does have a real impact on how fast we get around, and that impact is as real as the more-often-discussed impacts on emissions or fuel consumption. Maybe now I should buy that tiny little 1968 Fiat 850 Spider I always wanted.6

I haven’t discussed here some of the other factors involved, which some of the referenced authors do address. For simplicity’s sake I’ve focused on highway driving, but around town other factors come into play, especially at intersections. There is for example the typically larger turning circles of trucks and SUVs, which means they can take up even more road than their simple size would suggest, when getting through an intersection. And there is the familiar vision issue, wherein if you are in a small or low vehicle following a turning big SUV or pickup you hang back a bit (slowing traffic) while you wait for your line of sight to clear enough to make a go or no-go decision (as the big fella moves out of the way). Traffic professionals are very aware that an intersection that could handle 8 turning cars for every cycle of the traffic light, might handle only 5 vehicles if a few big trucks or SUVs were present.

Like so much in human life, what turns out to be optimal for an individual (big truck, great visibility, lots of cargo space) can be suboptimal for society at large (slower road speeds for everyone). But that is hardly a novel insight…

“The rise of trucks and the fall of throughput,” by Yang Gao & David Levinson

PCEs are not calculated purely on size. Other factors are taken into account, such as ability of the vehicle to accelerate and decelerate similarly to passenger cars, braking distance requirements, vehicle length as it impacts “gap acceptance” when drivers change lanes, width as it impacts driver comfort in adjacent lanes, etc.

As always, any garbling of research findings is my fault: please read the originals for the real goods.

Please note that in his own communication with the authors, David Zipper was told (and disclosed in his own writeup on their research) that they believed that the light-duty-only (SUVs etc.) impact on highway throughput (disentangling and removing the impact of heavy-duty commercial trucks) was about a 9.5% reduction in throughput. While I excluded this from my original post as I did not have direct access to underlying research showing this, I should have mentioned David’s comments, derived from his communications with the authors. Thanks for flagging this, DZ!

Because PCEs don’t matter if there are no other vehicles anywhere nearby.

Nope, it rusted away into a small pile of iron oxide shavings before 1970.