Revisiting the Grid

In which I update my priors

Please read the Caveat1 first!

A few years back I did a large literature scan for a client, hoovering up everything I could read (in English) about EVs. (This led to my weak joke that the only things that outnumbered EVs on the road were all the white papers, reports, op-eds, and journal articles about EVs.) I looked at customers, batteries, charging, costs, incentives, geopolitics, raw materials, emissions, the works. And of course the American power grid: was it up to the challenge of charging an growing installed base of EVs?

My conclusion at the time was that generation (the creation of electricity) would be up to the challenge (especially as the cost of solar power continued to plummet), as would transmission (the “wholesale” movement of electricity over long distances at high voltages), but that distribution (the “retail” movement of electricity over short distances from substations to customers, typically at lower voltages) would be a challenge, as expanding local substation capacity was always problematic. (There were issues of permitting, siting, reluctant local approval of unsightly industrial equipment, etc.)

Recently I have been updating some of those views.

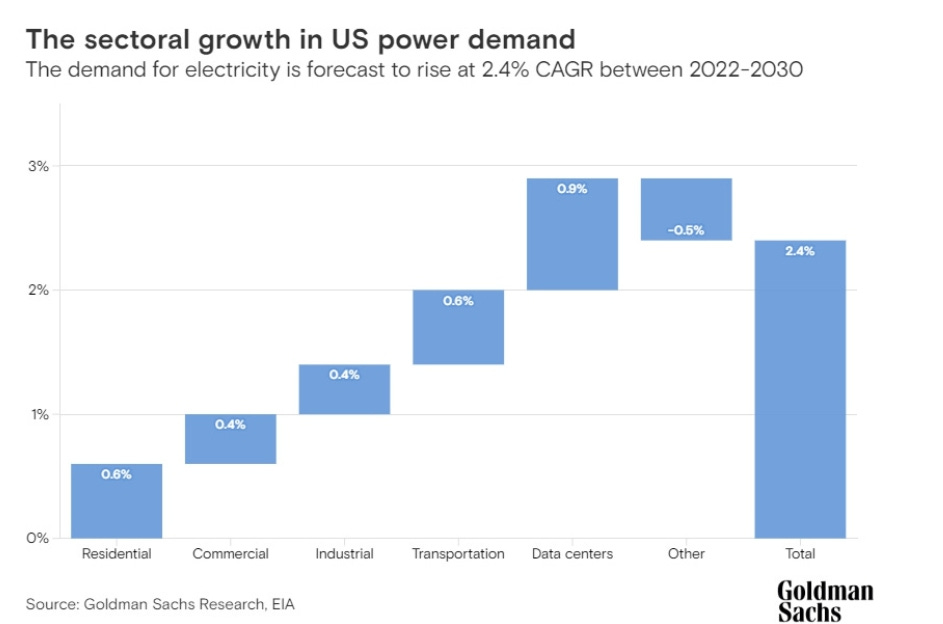

First: On the generation and transmission side of the equation, the rise of power-hungry artificial-intelligence-focused data centers may stress both G and T. This was unforeseen even a year or so ago, as a recent Goldman Sachs report shows: “Over the last decade, US power demand growth has been roughly zero, even though the population and its economic activity have increased. Efficiencies have helped: one example is the LED light, which drives lower power use. But that is set to change: between 2022 and 2030, the demand for power will rise roughly 2.4%, Goldman Sachs Research estimates - and around 0.9 percent points of that figure will be tied to data centers.”2

The forecasts I had looked at earlier included growth in Commercial, Industrial, and Transportation (mostly EV charging), but not this turbocharged data center growth. And while it is “only” a 0.9% CAGR, given the glacial speed at which American powerplants and transmission lines can be approved and built, this is a big problem.

Goldman Sachs is not alone in this projection. As UBS research asserts3 : “Data centers currently consume over 16GW of power, and we expect an additional 19GW by the end of the decade. This is largely due to generative AI [ artificial intelligence ] expansion, which layers onto the existing demand [ growing at a 15% CAGR itself ] from cloud services. Power availability remains a challenge. Sufficient power determines the ability to run generative AI training models.”4

For more color on this, see the excellent Construction Physics newsletter written by Brian Potter, specifically the How to Build an AI Data Center issue. As Brian writes (edited):

“Nine of the top ten utilities in the U.S. have named data centers as their main source of customer growth, and a survey of data center professionals ranked availability and price of power as the top two factors driving data center site selection. With record levels of data centers in the pipeline to be built, the problem is only likely to get worse. … Today, large data centers can require 100 megawatts (100 million watts) of power or more. That’s roughly the power required by 75,000 homes, or needed to melt 150 tons of steel in an electric arc furnace. … Data centers are still a small fraction of overall electricity demand… [ but ] SemiAnalysis predicts that data center electricity consumption could triple by 2030, reaching 3 to 4.5% of global electricity consumption.”

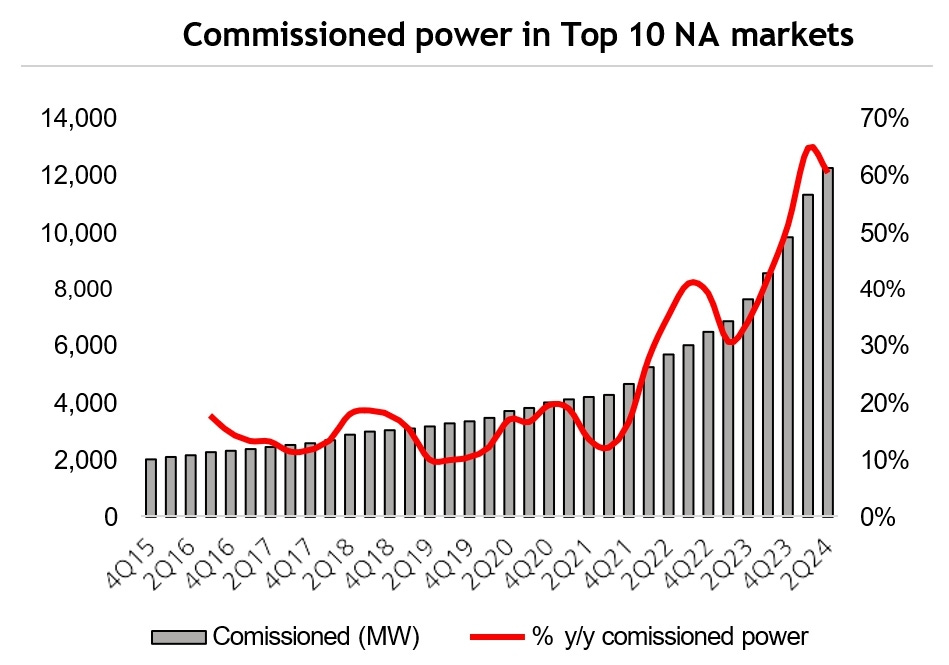

Here are two more charts to drive these points home, both from UBS. First, actual North American data center power needs;

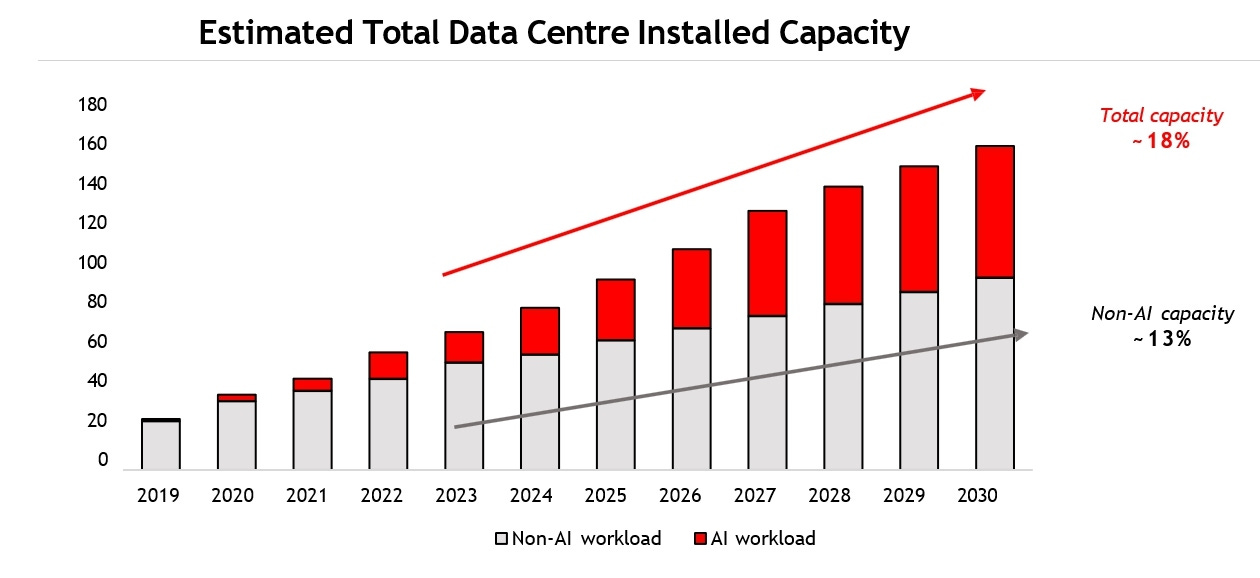

And second, also from UBS, the relative impact of surging demand for AI data processing, now growing (expressed as a CAGR) more quickly than ordinary cloud computing:

So my first revision to my views is that data center growth, especially as driven by the stampede into (computing- and power-hungry) AI will put more stress on the American generation and transmission system than I had expected. This will in turn put stress on the power supply needed to charge EVs. Yes, utilities will step up, yes DCs will get more efficient in their consumption of power, yes it is possible that AI enthusiasm will turn out to be a passing fad — but as things stand today, increasing AI DC competition for electrons may cause trouble for EV fleet growth.

Second: My other updating of prior beliefs is about the distribution system, the “last mile” (or so) in which bulk electricity is doled out to run stores and houses and… EV chargers. Here my update is not so much a revision as a confirmation. Research had indicated the distribution system (e.g. local substations) would be stressed by surging EV demand, but now we have new work out of California (UC Davis) which pretty much confirms that view.

I turn here to an excellent recent paper, “Impact of electric vehicle charging demand on power distribution grid congestion,” by Y. Lia and A. Jenna. This is as far as I am aware, the first authoritative study to look at distribution systems and EV power demand in a granular way, creating a real-world (vs. modeled) scenario.

First, two key definitions: “Substations are the connections that step down the high-voltage electricity from the transmission grid to lower voltages for local power distribution. Feeders, also called circuits, often refer to the conductors and transformers that deliver the stepped-down electricity to end-use consumers.”

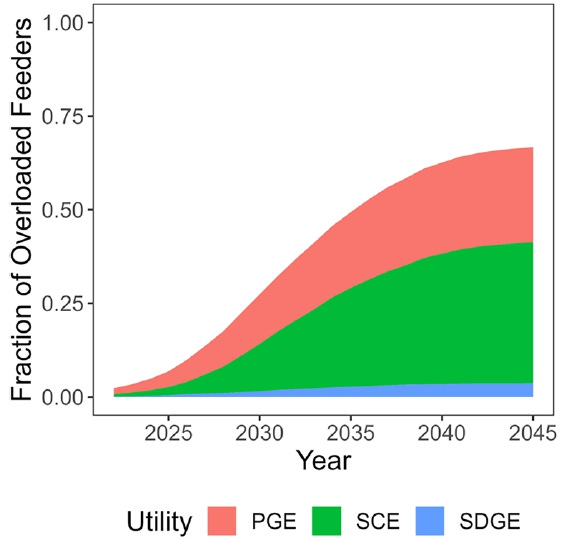

The study covers the entire distribution system in the territories of all three major investor-owned-utilities of California: PG&E, Southern California Edison (SCE), San Diego Gas & Electric (SDG&E), covering almost 90% of the population of the state: over 1,600 substations and over 5,000 feeders. In calculating the impact of expected EV demand growth (taking into account timing of charging, home charging, work charging, public charging, efficiency of charging, geography of charging, and on and on), they found that:

“The number of overloaded feeders ramps up rapidly from mid-2020s to mid-2030s, with only 7% of feeders overloaded by EVs in 2025, but that grows to a total of 27% in 2030 and 50% in 2035.” Thus this chart from the paper:

There is a cost to upgrading feeders and substations, but its impact is mixed due to the nature of electric power: even as money is spent on equipment, the increasing volume of power consumed kicks in, generating economies of scale, so the net impact on consumers’ power bills is mixed and may even result in reductions. In my view (this is not stated by the authors) the real challenge is not so much the cost of upgrading and expanding distribution, but the effort required, by utilities doing the work and governments working with citizens to allow often-contentious local permitting and construction to proceed.5

In summary (and remember, this is for California only, which as the biggest market for EVs in the US will see this grid crunch the soonest):

“On the aggregate level, we estimate that by 2035, 50% of the feeders in California will be overloaded by EV charging, and this percentage will grow to 67% by 2045.”

Thus I remain more convinced than before that distribution-level issues will be a real headache for widespread EV adoption in the USA.

Let me be clear about my own biases. I am writing this post not to pile on to the current “EV winter” sentiment. I personally believe, weighing all the evidence, that in the next 5-10 years EVs (counting both BEVs and PHEVs as EVs) will become a significant minority of US car sales, and possibly a majority soon after that. The technology is just too efficient, cost-competitive, and environmentally friendly to not assume a major role in our automotive market. But as always the automotive industry is a system, with many interlinked components. Switching out ICE for EV is not as easy an LS engine swap6 : lots of moving parts have to be orchestrated. There are ICE gas taxes versus EV user fees, reduced (maybe) maintenance budgets versus soaring collision repair costs, the trade-off between cheap Chinese EVs benefiting American customers versus possibly crippling American companies, and on and on. And today I’ve highlighted two more moving parts:

does the power demand that the AI that might someday drive our EVs reduce our ability to charge them?

and does a consumer’s desire to own an EV run up against that same consumer’s aversion to seeing a new substation appear in the neighborhood?

People hate trade-offs (see here, speakers off if at work!) but sorry, it’s what we have to deal with in the modern world, including the world of electric vehicles. I am pretty confident that we will work out all these issues, but work is what it will take.

Caveat: My expertise in things electrical is abysmal. In terms of electrical theory, it is limited to discussions of whether Bon Scott or Brian Johnson was AC/DC’s better singer. In terms of electrical practice, it is limited to, back in college, managing the mysteries of an early ‘60s Alfa Giulietta fuse box (Alfa’s electrics back them made Lucas look like a paragon of reliability). What you read here is derived from my reading of reports from real experts, which I have probably garbled. You Have Been Warned!

“Gen AI: Too Much Spend, Too Little Benefit?,” a Goldman Sachs Global Macro Research report released June 25, 2024, as Issue 129 in the firm’s Top of Mind series of reports.

See “Rapid data center growth will shift long term power trends,” UBS, June 21, 2024.

In the most ironic development I have seen in a while, it seems data centers are so hungry for electric power (for running both the servers and the cooling systems that keep them from melting down) that many DCs rely at times on diesel generators. Imagine that, our light and fluffy modern cloud computing (which gives off an aura of environmental friendliness) being powered by something as grimy and Old School as a diesel genset. But then again, see this (speakers off it you are at work):

Two developments could change the magnitude of these estimates (emphasis added). First, “improving EV energy efficiency from their current average efficiency to the highest observed efficiency can decrease the total capacity upgrade needs by 12%.” Second, “Removing all DC fast charging would result in a 12% drop in total number of feeders that need upgrade, and a 23% decrease in total capacity upgrade needs. On the other hand, if all public-charging events are conducted by DC fast charging, while the number of feeders that needs to be upgraded is only increased by 15%, the size of upgrade needs more than doubles due to the higher charging power demands. This implies that the adoption and usage of DC fast chargers need to be planned and managed carefully.” We Americans’ own impatience regarding charging speed may come back to bite us.

Sorry, you will have to look this up yourself, if you ain’t a gearhead already!