Staying Home, but Moving Out - updated

A look at the impact of WFH (work from home) on car demand

(See the footnotes for a small update.)

First, credit where credit is due: the gold standard of research on WFH is … WFH Research, which was founded by Stanford professor Nick Bloom and others in 2020, as it became clear what an impact the pandemic would have on working arrangements. Much of this post’s content is lifted from there, with gratitude; and of course any misinterpretations of their work are entirely mine.

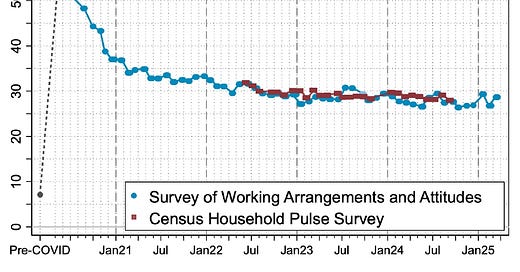

WFH existed before the pandemic, of course, but during that time it soared, as people avoided the office. Post-pandemic, the incidence of WFH has ebbed, as we all know, but seems now to have reached a new equilibrium (in the USA at least1 ) at a little under 30% of worked full-time days:

Source: WFH Research.

WFH numbers are notoriously squishy due to among other things definitional issues (“If I went into the office 2 hours one day, did I work from home that day or from the office?”), but let’s go with this 30%. On 5 days a week that is 1.5 days, but let’s round up to 2, because I can’t find my HP-12C.

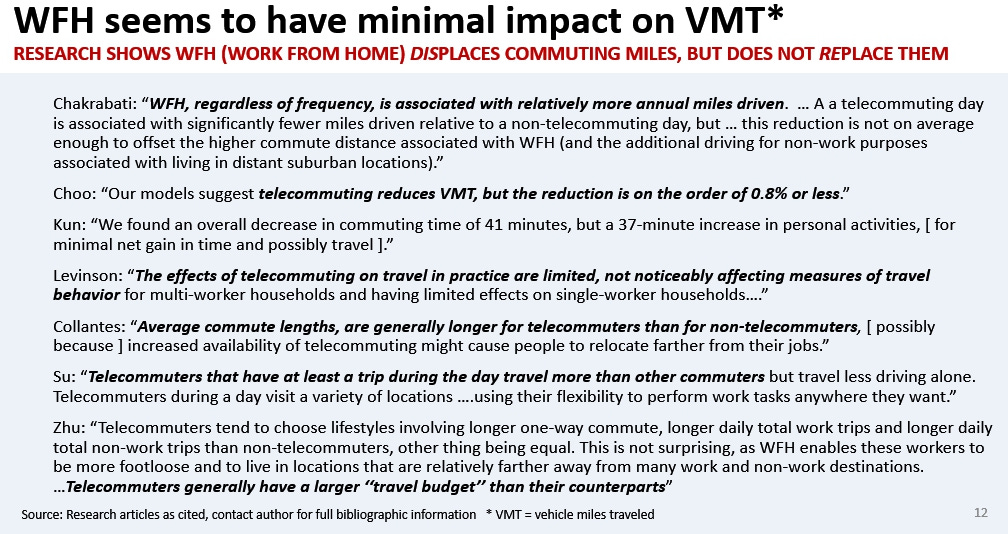

Simplistically, many observers believed that WFH would reduce VMT (vehicle miles traveled), as commuting dropped, and with lower VMT cars would wear out more slowly, and thus demand for them (thus car sales) would fall. As best as we can tell this never actually happened. Lots of reasons are given for this: I summarized some research reports in one of my Dealership of Tomorrow presentations a few years back.2

One of the reasons given, and this is the focus of today’s post, is that of increasing distance-to-work. That is, if I can work from home X days per week, then on the few days when I do go to work, I can tolerate a longer drive. Maybe not just tolerate, but welcome: heck, if I am in the office only one day a week I might be desperate to go there, and get away from the my barking and the 24-7 suburban leaf blower noise3. (The two factors could offset each other: if instead of driving to work 8 miles each way 5 days per week (80 miles), I drove in 2 days per week from my new house out in the bucolic distant suburbs (20 miles out), I’d still end up with 80 miles.

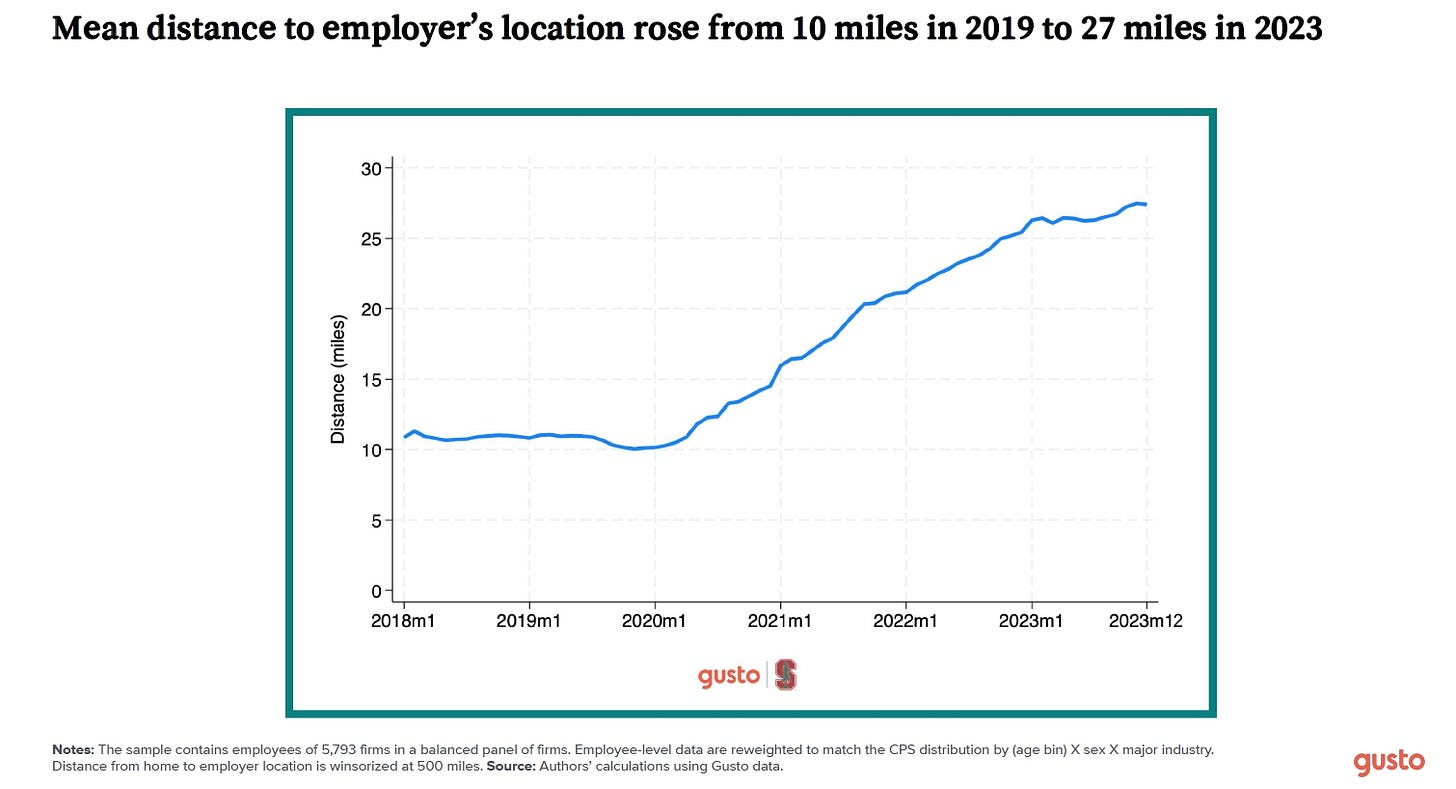

And of course WFH Research has some insight on this, shown here:

Yikes! If I take a mindlessly-simplified view of this, we’ve gone from 100 miles (10 miles each way, 5 days a week), to 162 (27 miles each way, 3 days a week). VMT goes up, and ceteris paribus so do car sales!

Now, there are so many things wrong with my simplification: sampling challenges, definitional issues, informal versus formal arrangements, variation by industry, self-reporting biases, etc. Please see the various research papers, as they all try to tackle this.

But very broadly speaking, among all the various threats to the auto industry (the cost of moving to EVs, dealing with tariffs, investments in autonomy, displacement of owned cars by ridehail or robotaxi, etc.4), at this gross level I tentatively conclude that of our 99 problems, WFH ain’t one of them.

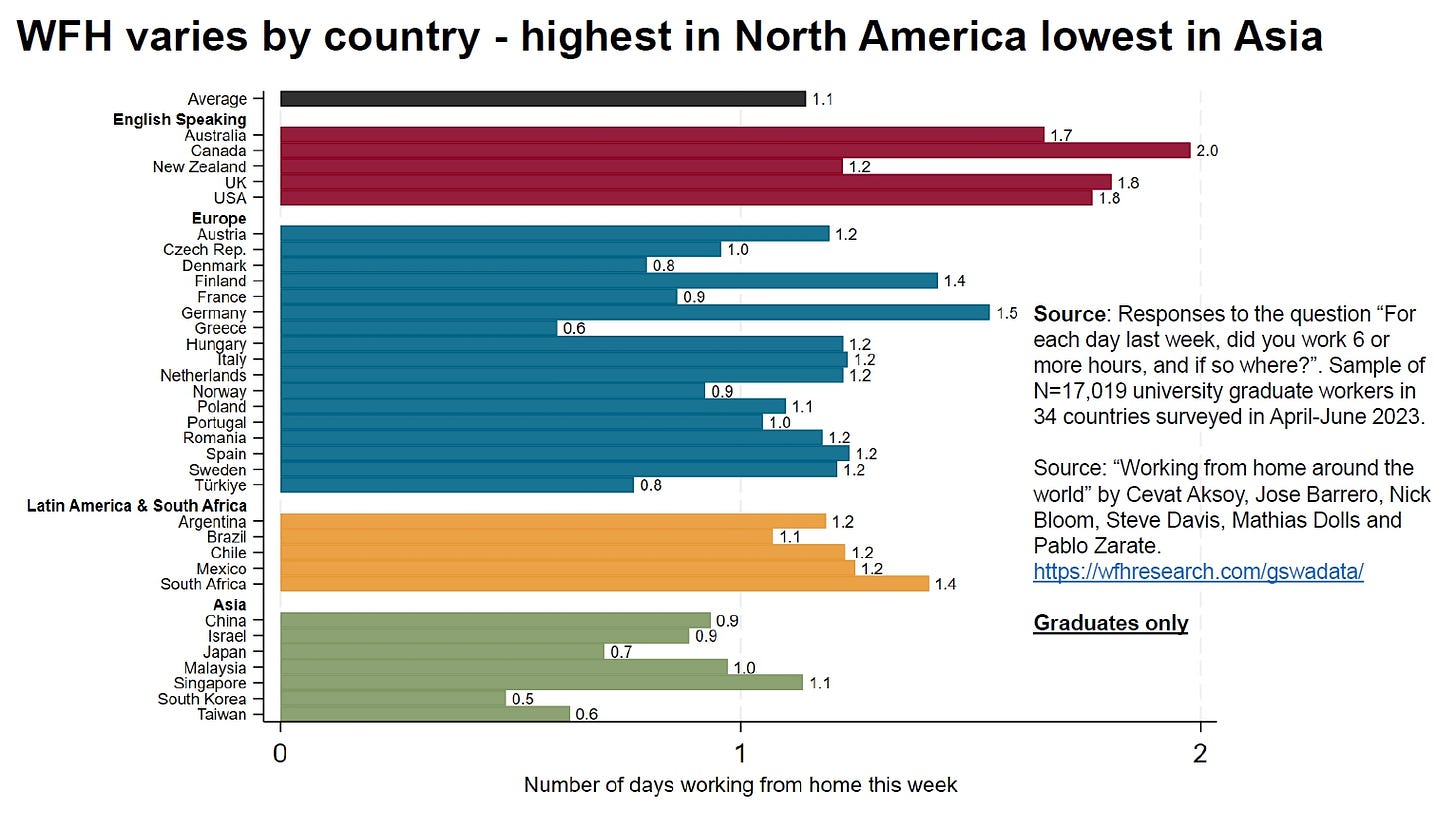

The incidence of WFH varies widely by country, as WFH Research has shown:

Insert here national-stereotype jokes about gregarious Greeks and Canadians frozen to their sofas on the prairies of Alberta.

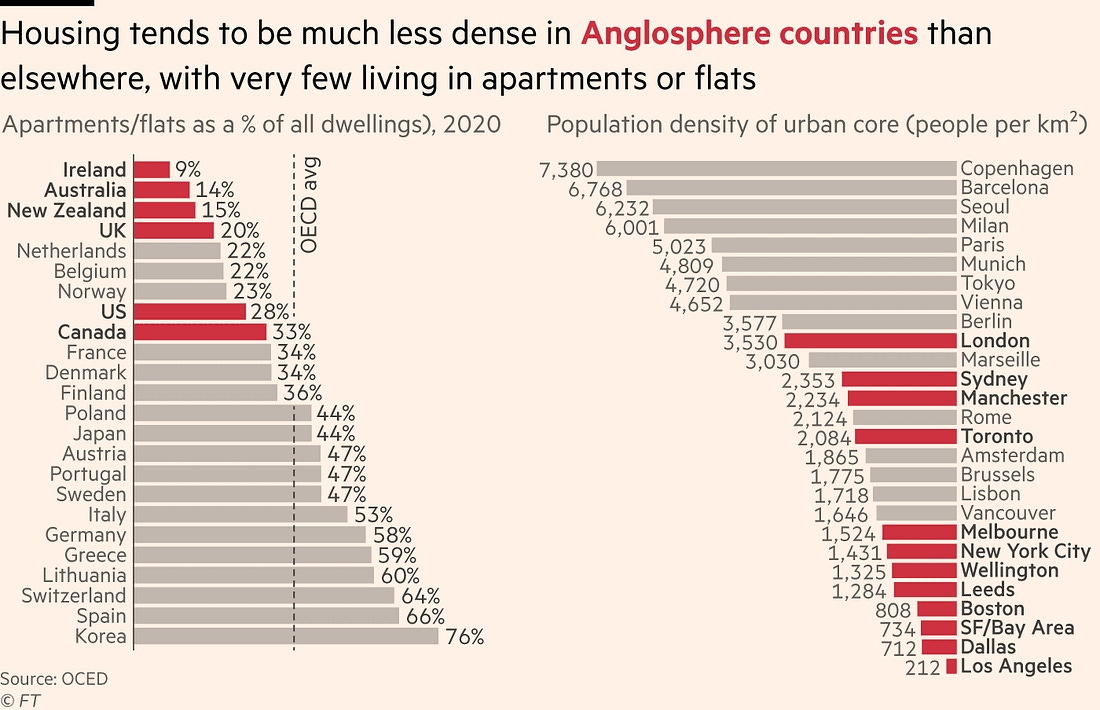

UPDATE: Nice chart from the Financial Times using OECD data, showing one reason countries are more or less receptive to WFH: if your home is a cramped apartment (versus a more spacious house), you may feel it’s worth the hike to a more spacious (?) office. (Also, the office coffee is usually free….)

The highest WFH countries roughly map to the lowest apartment-dwelling countries.

Also free coffee: I KNOW you are swiping extra Keurig pods from the office break room, am I right? You know who you are!

Did I mention tariffs?