Caveat: “All claims about Tesla are true, both pro and con.” An auto executive told me that once, and it is a very astute observation. Every word of praise for Tesla has an offsetting critique lined up against it, and vice versa. Tesla bulls and bears are thus well-armed with points both for and against, and talk right past each other. To (try to) avoid this happening with this post, please set aside your various biases about the company and just focus on the topic at hand: the Tesla product line. If you want to rant about Elon’s procreation strategy, or who really invented the frunk, there’s always Twitter.1

Most Car People will actually agree on one thing about Tesla: its Supercharger strategy is pure genius, and its execution of that strategy so far has been superb. (I am not so sure how the opening of the Supercharger Walled Garden to the sweaty hordes of EV newbies from GM and elsewhere will work out. Stay tuned.) But in my opinion Tesla’s other amazing achievement is mostly overlooked, and that is the radical simplicity of its product line. To cut to the chase, if Tesla can continue to make this product strategy work, it may redefine the way car companies have competed for the last century or so.

Why do I call this strategy “radical” simplicity? Because it is simple on at least three dimensions. First, Tesla has a simple portfolio of (barely) 4 products: S 3 X Y2. (Roadster will always be niche, and by the time the Cybertruck arrives, the X may be dead.) Second, Tesla has an extremely simple options lineup available per car. And third, while Tesla updates its cars’ software very often, it updates exterior sheet metal very slowly and very moderately.

Simple in models, in options, and over time.

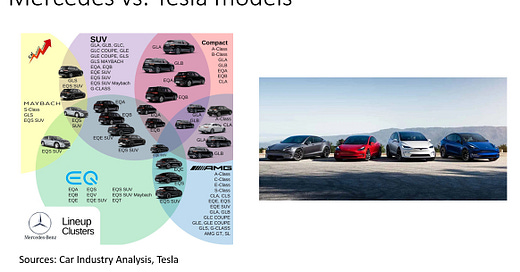

Time for charts. Let’s pick an OEM to compare Tesla to, to make the simplicity point. I’ll pick Mercedes, but feel free to nominate your own favorite OEM, the results won’t vary much. Tesla sold some 1.3 million units last year, and Mercedes some 2.0 million, with both in the plus-or-minus $50,000 price range (this of course wildly in flux with Tesla).

We’ll start by comparing model lineup simplicity:

(Yes, I know, everyone counts models differently, and one can argue if AMG is a trim line as opposed to a model line, but I think the point is clear regardless.)

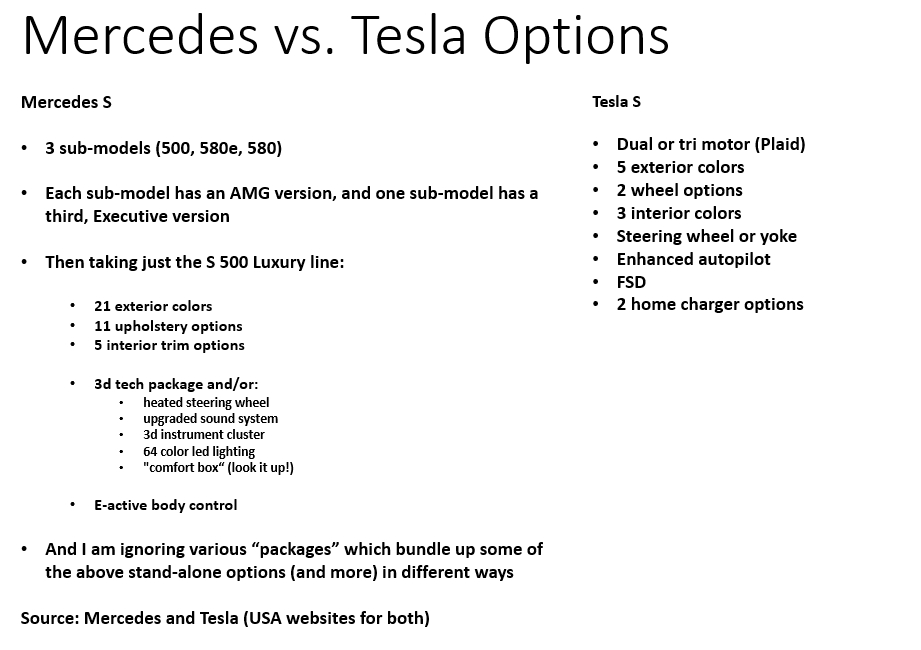

Now let’s compare options availability, choosing just the Merc S and the Tesla S:

And finally, we won’t need a chart for major model updates over time. Using the S versus S comparison again, the Mercedes has undergone chassis overhauls every 7 or 8 years recently (1991, 1999, 2006, 2014, 2021), while the Tesla S was launched in 2012 and remains on the same chassis since. (Both cars of course have had minor exterior styling changes, interior upgrades, powertrain revisions, etc.)

I think my assertion is proven: Tesla presents to its customers a very limited choice of models, with very limited choice in options, and with minimal changes in (hardware) choice over time3. And has been very successful with this.

Before we delve into the implications of this strategy, I do want to acknowledge that Tesla is by no means the first or only OEM to opt for simplicity. Arguably the Mazda Miata is barely changed in appearance and form since its launch in 1989: an example of simplicity over time. And some will assert that the Aston Martin product portfolio in recent years (prior to the launch of the DBX anyway) has been essentially an array of powertrain options across a series of very similar models: an example of model line simplicity. And in terms of options simplicity, low-cost cars have always trended this way: for example, the current Kia Rio (US version) offers only 6 paint colors, 2 interior colors, 2 trim levels, a Technology Package, and a few accessories like cargo mats.

But I will argue that no OEM serving the middle- or upper- end of the market4 has simultaneously enforced simplicity across all three dimensions of models, options, and time, all at once.5

And now to go out on a limb, since I know of no metric that can objectively measure this: Tesla, arguably, enforces a fourth dimension of simplicity, in that its cars all look alike (well no, not Cybertruck). As the excellent but anonymous Seeking Alpha analyst of all things Tesla, doggydogworld6 , has written: “Tesla essentially sells a single model with two sheet metal variants. Musk's unprecedented ability to sell 2m clone cars per year is a huge advantage...” Again, one can argue this point endlessly, but I for one will risk ridicule and admit that from a ridiculously short distance I can’t tell a Tesla 3 from a Y.

Anyway, onward.

So, assuming you buy my belief that Tesla’s products are “radically simple,” what are some of the implications of this strategy?

Before we go there, we should point out that this approach violates the rules of product strategy followed by virtually every OEM since General Motors’s Alfred P. Sloan laid out the famous “A car for every purse and purpose” slogan about a century ago. Ever since then we’ve been proliferating products, proliferating options, and refreshing products every few years (see any edition of the annual Bank of America “Cars Wars” report for specifics.)

It would seem Tesla is trying to overturn this model. Essentially, to make and sell cars as if they were cell phones: the physical phone looks mostly the same year to year, each maker has only a few models, and options if any are mostly in the software arena (e.g. bytes of storage capacity).7

So, implications. Observation #1: it is the most obvious thing in the world to point out that the benefits of this strategy to the manufacturer are immense.

First, it makes producing cars much easier and thus much less costly. I don’t know how much money per unit Tesla saves by cranking out a million or two “clone cars” annually, but it must be massive, as the scale and scope effects will be felt not only at the assembly plant level but all the way through the supply chain, which will offer lower prices for higher volumes of the same components. And it also makes product development much easier and thus much less costly.8 Easier to amortize the tooling in a gigacaster over 500,000 units than over 200,000.

Second, I will argue (as have others: see Steve Young at ICDP) that radical product simplicity makes a radically simple sales channel, the DTC (direct to customer) channel, more viable. Among other tasks, a distribution channel must help match production supply to customer demand. To the extent the OEM has made 14 of variant X and 78 of variant Y and 8 of variant Z, the matching task is harder, than if it just made 100 of X.9 (What if 4 of the 14 X orders cancel, and now we have to find new buyers for them? What if 8 of the Y’s are an exotic color that it turns out no one wants? These mismatches take hard work in real time to fix.) These issues are much more manageable if the factory offers a very limited range: “pick a color, pick some wheels, place the order.” Simplicity also allows the OEM to move more of the sales channel online10, since with every additional option one offers the consumer the likelihood of complex customer questions rises, and these usually require human intervention. (Questions like “Can I get the Comfort package with all the bundled options except the sunroof?”)

There are any number of other benefits to simplicity, of which I’ll list just a few here, without going into depth. Please add more! Marketing becomes easier and cheaper: I don’t have to advertise options and models, just the overall brand. Aftersales becomes easier and cheaper: I don’t have to stock and keep track of so many different repair parts. Labor becomes more efficient, in the factory and in the store: workers don’t need as much training and have fewer chances to make errors. We could go on….

It’s clear, OEMs would love to simplify. One giant factory, one model, no options, maybe just a website with a big Order button11.

There is only one problem, and that is the pesky, annoying, customer. Observation #2: supply loves simplification, but demand can set limits to it. The question is, will consumers, accustomed to the multiple dimensions of choice they have enjoyed for a century or so, accept simplicity?

The easy, short-term answer is “Yes, of course.” Tesla proves this. The Tesla Y was by some measures the best-selling car in the world in the first quarter of this year (leaving aside definitional issues about pickup trucks and cross-overs). Seems like a win for simplicity, at least to me!

But this answer leads to another question, which we have heard asked about Tesla repeatedly, in various fields: is this concept a role model or an exception?12 Every OEM CEO has to make this call, because if the former is true, that customers prefer or at least do not object to having less choice, then we are going to see product line and options pruning on a Biblical scale. But if the latter is true, and customers want to spec their car to the extent they now spec their Starbucks order, traditional OEMs should stay their variety-burdened course.13

And in my view the harder, long-term answer is “Maybe not.” We may already be at “peak simplicity.” Leading Tesla analyst Toni Sacconaghi (at Bernstein) has as usual very insightful comments on this, couched in terms of whether Tesla can meet its ambitious sales volume targets with a limited product line (emphasis added):

“Tesla’s volume ambitions represented massive outliers versus what was historically achievable. Given the competitive nature of the global auto market, dominant luxury cars ($45,000+) have historically topped out at 400 - 500,000 global sales per year, while the highest volume mass market ($25K- $35,000) cars and SUVs have topped out at 800,000 – 1,000,000 units per year, translating to ~10% segment share for mass market sedans and ~7% for mass market SUVs. Tesla’s volume goals were for Model 3 + Model Y to be 3 - 4,000,000 units, which represent nearly 50% of global market share in their categories. Notably, the Model 3 and Model Y have already achieved outlier volumes within their price segment, and were the #1 and #2 best selling luxury cars in 2022 - and yet they would still need to grow annual volumes by three times to achieve Tesla's volume goals. … We also note that in EVs, incremental volumes are typically captured by new models, which provides further reasons for caution about Tesla's ability to continue to grow Model 3 and Model Y beyond already impressive levels today.”14

(Note that he addresses both “model” simplicity and “time” simplicity.)

I tend to agree, that Tesla is pushing the limits of how much share you can take in a segment with a very limited portfolio of models, though of course I can’t prove the point. Maybe an analogy will help: is a car more like a phone or a house?

Silicon Valley denizens have always asserted the former: a car is a phone on wheels, you just have to get the styling right once, and then crank out millions of physically-nearly-identical units, only upgrading the electronics and software along the way.

But if a car is more like a house, complexity re-enters the picture. House buyers like to specify square footage, number of rooms, flooring, countertops, appliances, window treatments… and we haven’t even gotten to the furniture yet.

A car is somewhere in between. History says customers like choice, Tesla says they don’t, really … and they haven’t been wrong, so far. (Though if Tesla is reading Toni’s work they may be thinking about accelerating their historically slow pace of new model launches.)

The choice now facing rival OEMs — simplify or not? — is, I would assert, as big a decision as how fast to go all-EV, or how to source car software. Yet is is hardly discussed, though I believe this is indeed Tesla’s other great achievement, right up there with the Supercharger network.

So far…

Well, maybe not always: mercerglenn at Threads.

Thanks, Ford, for screwing up the acronym!

While I cannot say with certainty that it is the simplest offering available, because to do that I’d have to look at every OEM’s offering, and rank order them all, and I am much too lazy to do that, I am pretty sure of this — but would welcome any reader pointing out a simpler OEM, in the same volume range, of course.

Tesla argument #37b: is it a mass market car? a luxury car? a premium car?

Maybe I was too influenced by Everything Everywhere All At Once.

I know, it’s a bizarre handle, and seems to come from the popular corruption of the old phrase “It’s a dog eat dog world” after Snoop Dog released “Doggy Dogg World” in 1993. Maybe our commenter is implying that there is fierce competition in the car industry.

Given where Tesla is based, it only makes sense that they would follow this iPhone path.

I mean, how cheap is this product adjustment, a “reacher stick,” to enable drivers in the UK and elsewhere to drive LHD Model S’s in their RHD country? bit.ly/44BHGBV

You might say here, “Wait a minute, don’t we get around this by moving to true BTO (build to order)?” Then we never make an unwanted unit. That’s true, but virtually no OEM, even Tesla, works on a true BTO basis. The pressure of high fixed costs at all OEMs drives them to keep the factory running regardless of order levels. No OEM wants to generate a “bullwhip effect” in its supply chain (Google it!) by jerking parts orders up and down. Or to send all its workers home on Tuesday, only to ask for double shifts on Thursday. But radical simplicity allows a factory to move to “virtual” BTO by just making batches of cars (e.g., 100 red ones then 100 blue ones) and allocating them to orders as they come in.

I don’t want to conflate online/offline and DTC/dealer: one can have a dealer channel that works mostly online and one can have a DTC channel that works mostly in the physical world (see Starbucks).

I realize I may have just described Trabant, minus the website. Digression Alert! But let’s face it, socialist-states-that-have-become-dictatorships love simple product lines, because they are consistent with Marxist thought. If there is no higher authority than the Workers, then once the Workers have chosen the ideal car, why would the State ever produce anything else? (Separately, dictatorships tend to hate cars, since they allow citizens to just drive off when and where they please, making them hard to monitor and control: in effect, cars are Freedom Machines. Much better to pack the people into trams, where we can keep an eye on them. This tendency also explains why Soviet and Warsaw Pact cars were so awful: these countries really didn’t want to make them at all, but they had to produce them if only to keep up the appearance of economic competitiveness with the West. Can you imagine James Bond trying to escape the Stasi by crashing through Checkpoint Charlie in a… Wartburg?) End of digression.

Examples of each: completely integrated software: role model; steering yoke instead of wheel: exception; both: Supercharger network (great first-mover idea, probably harder now for follower OEMs to emulate); both: Elon Musk (marketing genius, PR nightmare).

Not that OEMs haven’t addressed this issue in the past. I have been hanging around the auto industry since the1980s, and among others there are two truisms one could rely on for the 40-plus years since then: 1) periodically every OEM will announce its intention to prune platforms, models, variants, and options menus; and 2) every one of these plans will sooner or later fail, as the pruned product line soon starts sprouting back models, variants, and options. The industry has never successfully trimmed customer-facing variety (even as it has, I will admit, done wonders with parts and component sharing that the customer does not see).

From “Why isn't Tesla seeing more price elasticity?”, April 25, 2023.