Warning: long dull post and a really dull chart. You have been warned!

Everywhere around the world there is an ongoing debate about whether direct-to-customer distribution of cars (DTC) or indirect distribution (IND: wholesalers, agents, dealers, etc.) is superior. I won't weigh in on my view of this here, but will point out that this debate almost always omits two key realities, regardless of where you come out on the DTC vs. IND question.

First, though not the main point of this note, the debate usually conflates “new car dealer” with “new car sales” (we are ignoring here used-car-only stores). Of course, without sales of new cars there would be no reason for either IND or DTC stores to exist. But, once there is a flow of new cars out of the factories, IND and DTC stores usually can and do take on other functions. These include:

service of cars (which is comprised of both parts and labor, and includes factory-paid recalls and warranty work, customer-paid maintenance and repair, and internally-paid reconditioning of used cars),

arranging of financing of cars (cash, lease, loan, “subscription”),

and used car operations (purchase (often as trade-ins), refurbishment, and then resale of used cars).

Additional functions can include collision repair (usually handled separately from regular service: note even Tesla does regular service in-house but often out-sources collision repair), car rental, the sale and installation of accessories, and more.

The point of running through this long list is that any debate which focuses on the new-car-sales function only will provide an incomplete answer to the question “What is the best distribution channel to use?”

(In many cases, in fact, the channel (as distinct from the factory) will derive most of its profit not directly from new-car sales. Thus in 2018 (I am using a pre-Covid pre-chip-shortage year), the average US dealer made 25% of its store-wide gross margin from new sales, 25% from used sales, and 50% from service (NADA data). The situation is different at the factory, but even there the new car itself is not the whole story. One only has to look at the prices of, say, BMW repair parts to realize that the oft-cited assertion is true: sales of such parts can generate half of an OEM’s total profit.)

But let’s move on to the second missing part of the debate: when we argue about new-car sales channels, the discussion almost always flows from customer-back rather than factory-forward. That is, most of the debate revolves around what the customer wants. And of course this is a crucial perspective, in fact probably the crucial perspective! But it is not the only perspective, as the realities of car production must be considered as well.

And taking these into account helps explain how the current indirect distribution system came to be dominant, as it was not always so: in the early 1900s, in the USA at least, factories sold cars from their own stores, via traveling salesmen, and even by mail order (essentially a primitive internet!), before evolving the franchised dealership system. And even today, in the face of incessant debate about customer satisfaction (or lack thereof) with dealers, production factors can help explain why the IND channel is dominant virtually everywhere in the world. (Even China, which had a clean sheet on which to design its new auto industry, chose to mostly replicate the Western dealership system.)

I think there are at least two production considerations which tend to push the system away from direct sales (DTC) and to indirect sales channels (IND), and neither has anything directly to do with the customer’s needs and wants. These are supply-side issues.

1. IND buffers TOTAL production. The break-even point for an average car factory is about 80% or so - even Tesla Fremont is thought to be in this range. Thus the factory wants to run as close as possible to full, all the time. Good research from the International Motor Vehicle Program also shows how the capacity/cost relationship is not 1-to-1: a factory cutting back from running 100% full to 50% of capacity results in costs dropping only by about 20% in the short run1, since such cuts trigger massive and costly ripples through the whole supply chain. But intermediary-owned inventories buffer the factory from total demand fluctuations (which can be triggered by bad weather, holidays, income tax refunds arriving, recessions, etc.) in terms of both volume and revenue. In down-cycles independent intermediaries load up on inventory, and step up sales efforts; in up-cycles their inventory dwindles, and they shift to order-taking. In down-cycles intermediaries’ profit margins fall, and in up-cycles they rise2. In terms of both units and dollars, the IND channel acts as a flywheel or buffer for the OEM. In short form, the IND channel allows the factory to supply cars at an optimal cost point, even as demand whiplashes up and down.

2. IND buffers MODEL production. Every car company sooner or later makes a “clunker” of a model. Or it overproduces a sedan version when the market decides it wants a coupe. It is hard to quickly cease, reduce, or reverse production of these, both for immediate economic reasons (penalty payments to suppliers) and longer-term strategic reasons (“We need a model in that market niche to remain competitive.”) IND systems (and no intermediary or OEM will ever say this in public) can more effectively move unwanted metal than the DTC system can. Yes, they do this by selling the customer something the customer does not want3. This is heretical to say out loud in the modern world, but it is true. We all know that if the factory has Edsel’s rolling off the line at 60-second intervals day and night, it will thank God there are intermediaries getting them sold (rather than having them pile up outside in the factory parking lot)!

The question arises, then: why are intermediaries better at doing this than DTC factory stores or websites?

Because independent intermediaries can more effectively execute PRICE DISCRIMINATION (PD). Customers cringe at the word “discrimination,” because they sense that it prevents them from getting what they consider a fair price – under PD, different customers do pay different prices. And since customers don't know what a fair price for a car should be, they define it as "what the other guy paid.”4 And so DTC companies like Tesla generally go with "one price, posted online, transparent, same for everyone." Zero price discrimination! All the guys pay the same price! But with IND channels, you can execute PD, which may strategically be unwise (customers don’t like it and so may migrate away from the brand using it, maybe) but which tactically, over the short run, may be very valuable, especially when demand is below supply. Let’s look at examples, to make this clear.

Assume a DTC system. Take rising demand (D), greater than supply (S). Assume a car sells for $100, we are selling 10 units, and our break-even volume is 9. Let’s say demand is for 11 or more, people love our cars. We have the ability now to issue an across-the-board price hike to $110, we sell 11 units at the level, revenue goes from $1000 to $1,210, there is joy at HQ!

But the reverse dynamic also holds, though no one wants to think about it.

Take falling D, now below S. We are at $100, we are selling 10 units, demand at that point is for 10 or less, we are perilously close to production break-even. So we issue an across-the-board price cut to $90, we sell all 10, revenue falls from $1,000 to $900, ugh. This is what has been happening to Tesla. (In the language of economics, when pricing is direct to the customer from the factory, and therefore completely transparent, the marginal price instantly becomes the average price.) And customers who would have been happy to pay $100 get a free $10 discount they didn’t require!

But if we had an IND system, we could leave the posted price at $100 and give the channel (dealers, agents, fincos, salespeople, etc.) a $5 payment, which they could apply in whatever way they find would get the car sold. If customer A will pay $100 anyway, the channel pockets $5. If customer B would pay $100 but thinks his trade-in is worth more than the market does, the intermediary can give her a $2 over-allowance on the trade. If customer C would pay $100 but can't swing the monthly payment, the finco can subvent his interest rate. Or I can just tell my channel partners “Take a small loss on this car and I promise you will get extra supplies of our more popular models.” &c., &c. Thus we get 10 cars sold for a net $95, and revenue is $950, which is not so bad a drop. Marginal price does not become average price: we might end up charging ten customers ten prices.

And, if demand is elastic (greater than 1.0, which is often the case with cars), I not only get more revenue for my ten cars, I sell more than ten cars. (Those extra cars at lower prices of course may be selling at a loss on a fully-allocated cost basis, but can still provide some positive contribution margin.)

Thus we avoid what some used to call "The million-dollar Taurus:" a visible across-the-board $1,000 price cut to sell the 1,000th Taurus flows instantly to the other 999, whose customers have now received almost a million bucks' worth of discount they didn't need.

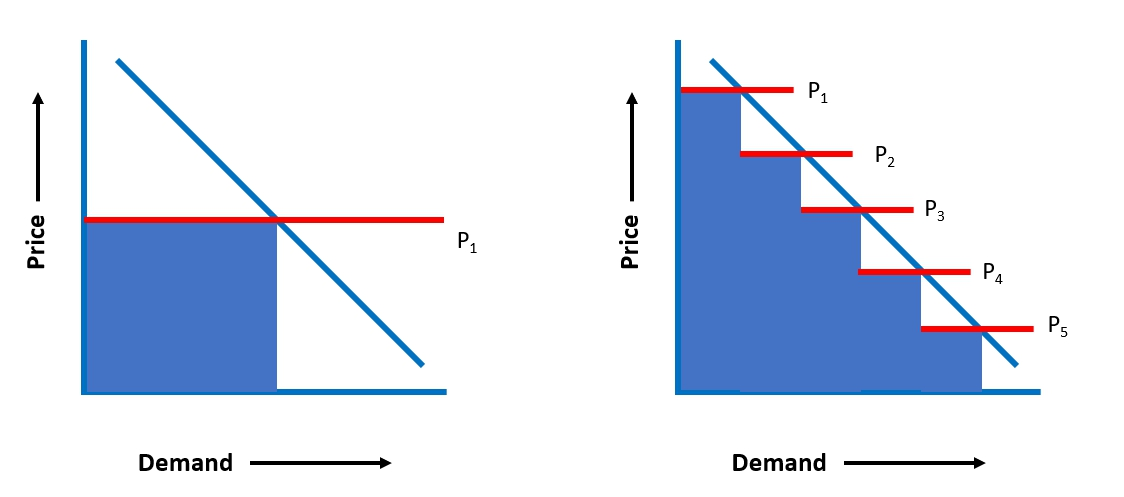

The chart below (yes, finally, we get to the chart!) shows this in Econ 101 terms. The demand curve slopes down to the right: as price is lowered (the red line) unit demand increases. Revenue is the area under the curve in blue: units sold times price. On the left we have one price (thus no PD), and sell all 10 cars at one price. On the right we have PD (here, 5 prices) and sell more than 10 cars, for a range of prices, and for much more revenue: the area in blue on the right is larger than the area in blue on the left5

I don't know how valuable price discrimination is for any particular car or car company: I don’t have access to OEM calculations of their demand and price-elasticity curves. But in the last half-century or so, with S almost continuously greater than D, the ability to execute PD helps explain why in almost every country OEMs use IND: intermediaries such as dealers can move the metal more price-efficiently than the OEM, by maximizing price on a customer-by-customer basis6. Then, in the last few years, with D above S for a while, OEMs fell in love (again) with DTC. If S moves back into line with D, we shall see if this particular love affair holds.7

We can see in today’s real world a clear example of DTC’s inability to do PD, in the case of Tesla. As demand for Tesla vehicles softens (slightly!), to sell 1 more Model Y the company must cut the price to all the other Model Y’s, because there is no channel intermediary willing to share management of this particular burden, via localized, customer-specific PD.

Again, in the long run, strategically, I won't assert that DTC is better or worse overall than IND. (The answer would probably vary by country and OEM anyway.) In fact my bias is for a blended system8. But tactically, over any short term, IND can execute price discrimination more efficiently, with targeted rather than across-the-board discounts.

Over a longer period, for example longer than a year, costs may fall an additional 20%, but the full 50% is never made up.

Thus, speaking somewhat cynically, OEMs become more interested in alternative sales models in upturns (when intermediaries capture more profit for themselves), and fall silent in downturns (when intermediaries are sharing in losses along with the factories).

Or rather, does not entirely want: maybe the car is blue and the customer wanted red, maybe it has a CD player when the customer wanted an 8-track. (Showing my age here….)

The joke goes that customers don't necessarily mind paying MORE for a car, only to be sure that no one else paid LESS.

The slope and shape of the demand line reveals elasticity: a straight 45-degree line like this implies perfect elasticity (e=1.0, so a 10% price cut = 10% more volume sold) at all price points, which is unrealistic.

Does this result in less price transparency and more complex deals? Sure does! Do customers like this? Sure don’t? Actually, probably most just don’t care one way or the other. And some actively like PD, because it lets them feel they they somehow outsmarted the dealer and got a better deal than other customers. If you think of yourself as a champion price negotiator, you probably aren’t going to like buying a Rivian. But as I said at the outset, I am talking here about supply-side logic, not demand-side logic.

And, to drone on a bit longer here, customers don’t necessarily hate PD, given they put up with it in most products, not just cars: yeah, I’ll pay more for the plane ticket if I wait until the last moment; yeah, I’ll pay more for the cookies if I buy them at Whole Foods than at Aldi.

A colleague put it to me bluntly: “When D is greater than S, any sales system will work. You could auction cars, raffle them, drop them from blimps. But when D falls below S, then you need to enlist a fleet of highly motivated intermediaries to make the factory’s problem go away.” To be fair , most OEMs utilize hybrid systems already, in a limited way: retail sales tend to be IND and fleet sales DTC.)

Even companies that car OEMs hold up as exemplars of DTC sales often use blended systems: Apple, for example, sells iPhones DTC on its website and in its stores, but a majority of its USA sales use IND channels, mostly the phone companies.