This will be a long post, because of course China is now an automotive superpower, and as such its decision to begin exporting in volume is more than significant. It’s been long awaited and long deferred: remember Malcolm Bricklin’s Visionary Vehicles, from the early 2000s?

Acknowledgments. As always, I want to thank all the analysts and observers I have learned from. As my readers have certainly noticed, I have no access to any primary research of my own, and so I depend on the good work and the good will of all the industry analysts out there who are generous enough to make their work available1. They deserve credit for their work, just as I must accept responsibility for any misinterpretation of it: those errors are entirely mine. I encourage you to employ their services when you can, as they earn their living doing this. (I, conversely, write these posts just for fun. But then again, my price is quite affordable, at free!)

Enough preamble. 向前!2

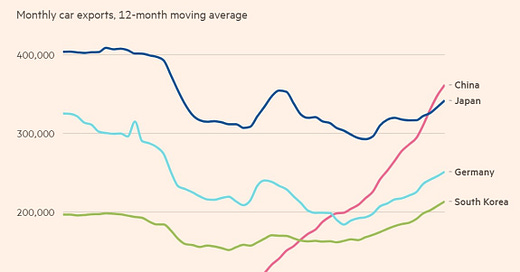

China is in the midst of a light-vehicle export boom that shows no sign of quitting. In fact, the country will likely soon conclusively surpass Japan as the world's biggest exporter of light-duty vehicles. The implications for markets and makers around the world will be profound, as they were during the first two waves of export expansion from other Asian countries: Japan from the 1970-80s onward, and Korea from the 1980-90s.

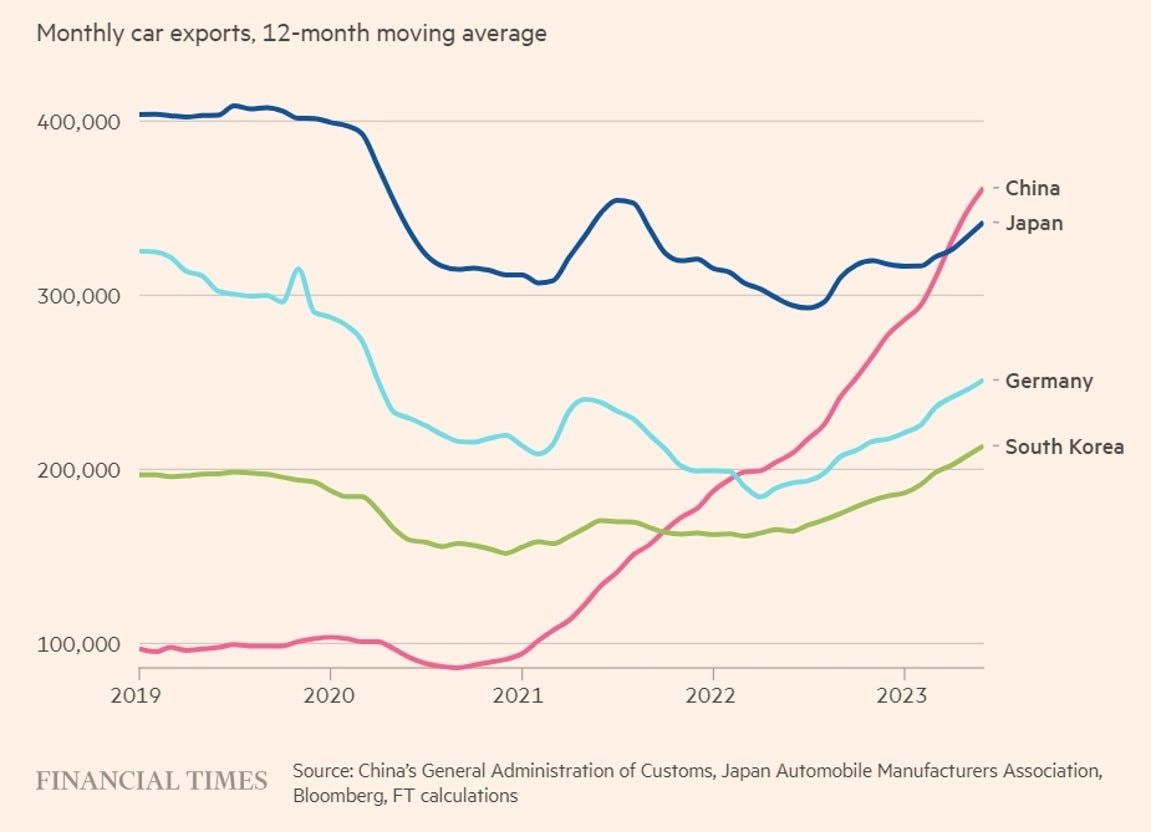

Industry observers may be forgiven to some extent for missing the first two waves (for example, it was not easy to predict the oil price shocks of the 1970s that supercharged Japanese exports), but this time around we should have seen it coming, as the Chinese central government announced its intent to grow its industry into "a dominant global player" at least as far back as 2015, when the 10-year "Made in China 2025" plan was released. (See the key PDF file at the end of this post.)

And while many of us like to bash governments everywhere for their incompetence, well, this time around this Beijing proved quite competent, as we can see from how domestic Chinese firms have indeed risen into a commanding position in the home market.

And now, with the home market secure, it is time to look outward. The export drive is on the ICE side enabled by low production costs at home, and on the EV side by China's massive lead in battery and associated technologies.3

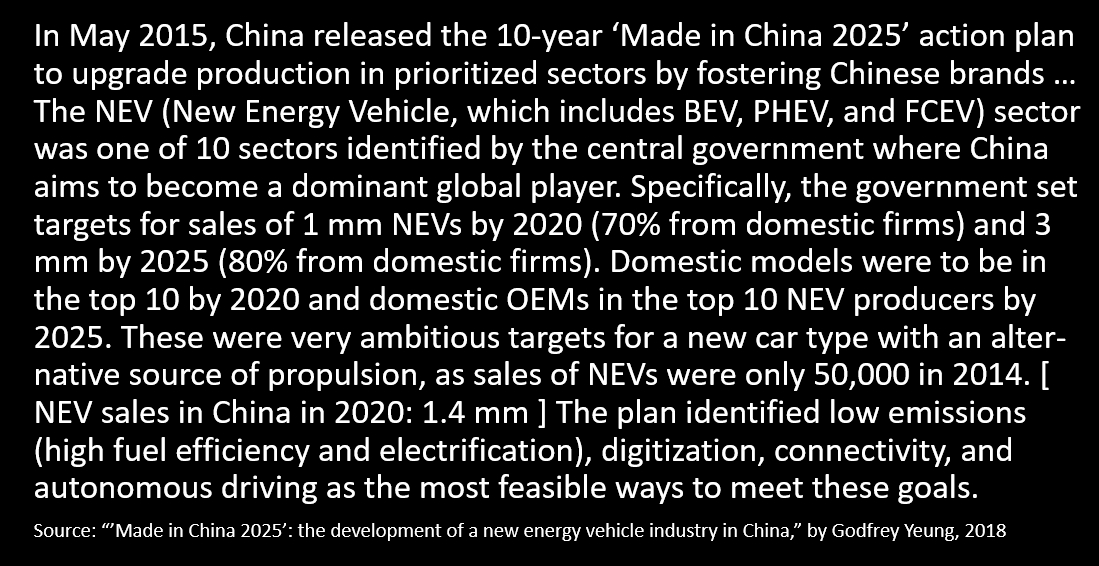

And the Chinese move fast: in the markets they have targeted, their share growth appears to be outpacing the rates set by the Japanese and Koreans decades ago (and even perhaps Tesla). Our thanks to the good folks at Bernstein for this complex but excellent chart showing the relative pace (in Europe) of BYD against Toyota, Hyundai, and Tesla.4

Europe is indeed the richest target of opportunity for China, as it is a wealthy market (thus able to pay for EVs), a green market (thus eager to accept EVs), and a mostly (to date) open market (without the barriers the US presents, as we will see below).

By the way, one unfortunate tailwind filling the Chinese sails blows from Russia. With that country's invasion of Ukraine various "Western" OEMs ceased supply of cars to Russia, and China has stepped in to fill the gap. (And if you're wondering about Belgium's place on this chart, please note that this country has no peculiar preference for Chinese cars, but that it serves as a major importation point for Chinese cars headed to various destinations across the EU.)

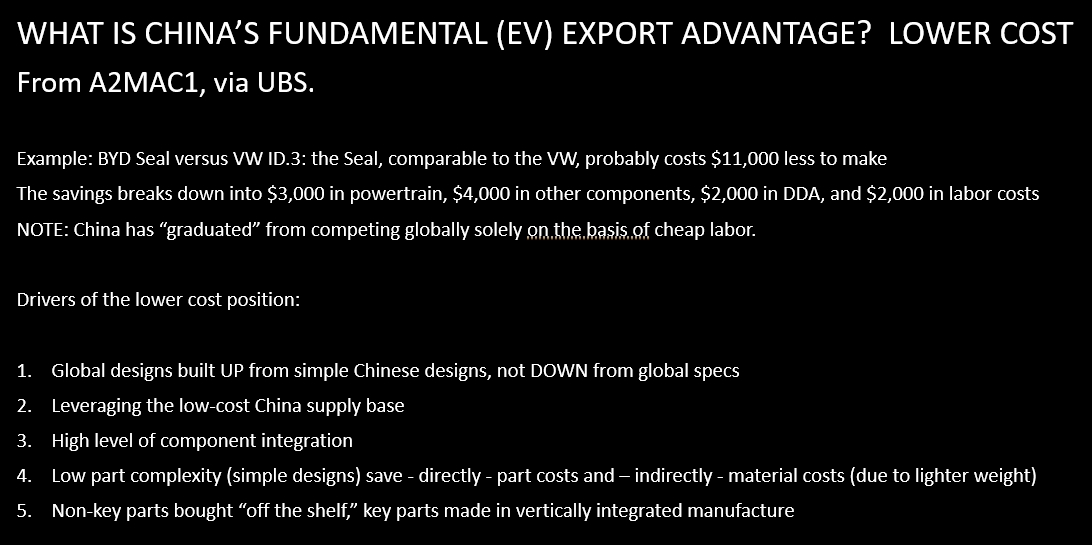

As noted, it is the Chinese edge in EV costs and technology that is really powering their export surge, and we can turn to the experts at A2MAC1 (publishing jointly with UBS) for details on this, as they compare a BYD Seal to a VW ID.3. As a historical note, 20 years ago this chart would have been (in my opinion) all about lower labor costs in China: today it is about lower costs generated not just by cheap wages but by mastery of technology, control of materials, and construction of a local supply base. A pretty amazing achievement indeed!

Before we all go too far off the EV deep end, as it were, I must thank Gavekal Dragonomics for pointing out that China is exporting Old School ICE cars at about the same rate as Brave New World EVs. I assume this is both because there is a market for ICE still (certainly Russia, but also in developing markets) and because Beijing would love to soften the blow of the EV transition for ICE-building Chinese OEMs, by providing them with an export outlet for their gasoline capacity.

Of course, one large developed market which one might think is a target for Chinese exports is pretty much not in the cards any time soon: the USA. For one thing, the Trump-era 27.5% punitive tariff against Chinese cars has been left intact under Biden, and even if that ever goes away we still have here the 25% tariff on imported trucks (and pickups are where the Detroit 35 make their money). Then there is the fact that no Chinese EV would qualify for Biden/IRA retail incentives (of up to $7,500 per car). Thus when S&P (IHS) looks at BYD exports, for example, they don't see the USA cracking even the top ten list of destinations any time soon.

(That being said, I can imagine Stealth imports of Chinese EVs into the USA, via JVs with the home team. I call these Stealth units since we recall the Dodge Stealth was a rebadged Mitsubishi 3000GT. The D3 used to have numerous Asian JVs they relied on to plug product gaps where they were uncompetitive: recall Ford/Mazda, GM/Suzuki, Chrysler/Mitsubishi, and more.)

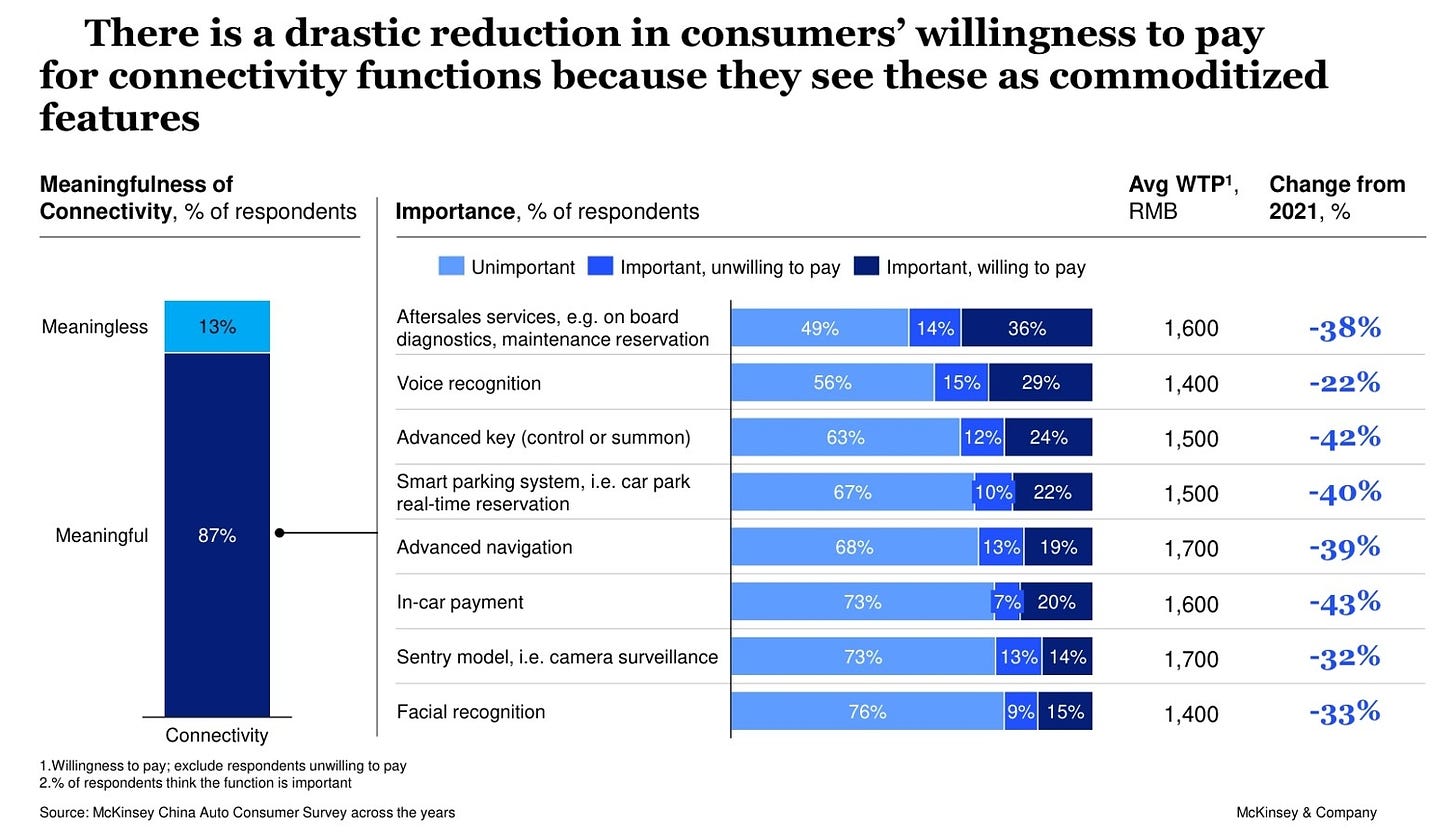

As the Chinese OEMs gain their footing abroad, we may see a secondary competitive effect, beyond just erosion of incumbent market share. By this I mean that the Chinese may shift the basis of competition. We've already seen this happen in the past: for example, the Japanese brought better vehicle quality to the masses, so that incumbent OEMs had to mend their shoddy ways. The dimension the Chinese may add is described as "the intelligent cockpit,” wherein advanced electronics, sensors, and software transform the car's interior from a fairly passive collection of knobs and vents to an active assistant or even concierge for driver and passenger. The exhibit below lays out some details on this. I do not know if traditional OEMs are ready to compete on this front - especially as Chinese firms are offering not just more features but higher performance versions of them. For example, in-car IT that boots up as fast as the engine or motor starts: no more annoying "waiting for Bluetooth" messages, etc.

And there is no reason to believe the pace of innovation (and thus competitive pressure) will ease in this arena, as Chinese tech companies are crowding into the automotive space, eager to deploy their skills in cars. (See for example Huawei, with its Arcfox, Luxeed, and Aito auto projects). I keep wondering what is holding up the firm I would think is the most likely to raise an American response to this challenge: Apple. Rumors of the Apple Car have been circulating for many years, but they remain only rumors.

There is a downside to the intelligent cockpit: not only will it be costly and difficult to compete in this space, but customers may not be willing to pay much for OEMs' efforts. As data from McKinsey shows, in China at least no sooner is one of these features introduced than do customers decide it is a commodity and so not worth paying extra for. (This is a primary reason I am not personally bullish on OEMs' ability to generate massive revenue from so-called "connected car" features.)

(Note that 1,600 RMB is about $220.)

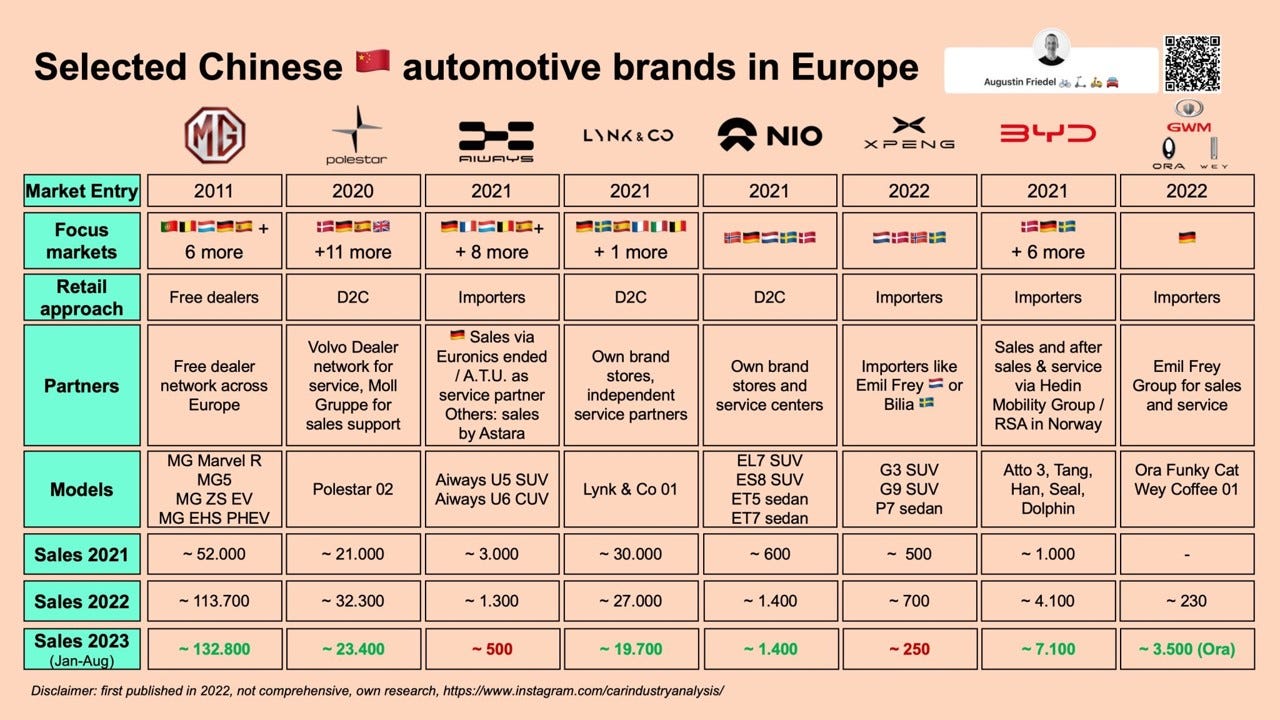

I'll close with one last chart, this time on distribution. The Chinese OEM export wave is all about newness, novelty, and innovation, from EV powertrains to exotic heads-up displays. But in one arena these OEMs remain relatively conservative, and that is in how they distribute, market, and sell their cars. Let's take a look again at Europe, thanks to the excellent Augustin Friedel. Here we see the main Chinese entrants lined up and compared on various dimensions.6 Now take a look at the Retail Approach line: they could have all gone to Europe with a Tesla-inspired D2C (direct to customer) model, but they did not. Even the three who sell by D2C do service with partners, except for Nio. (And according to Reuters, sales in Europe have not met Nio’s expectations, such that the company is now evaluating using dealers in key European markets.). I know I am biased in favor of the dealership model, but it is still a fact that as the most advanced EVs in the world enter Europe, they mostly retain a distribution system that has been around for a very long time: Emil Frey as a company is just about a century old, I believe. Sometimes tried-and-true has its advantages, even when shooting for the moon.

If any source would prefer I stop citing their work, just let me know and I will desist.

Onward! (I think.)

It is my view, entirely based on opinion and with no recourse to facts, that China waited this long to export because first, the domestic market was growing so rapidly that it sucked up all production capacity, and second, because the EV technology lead was not secure until now. China needed the EV edge (again, in my opinion) because the traditional route to export success in developed markets, to lead with low cost, as the Japanese and Koreans did, has now been closed off. This is because good, clean, and reliable late-model used ICE cars are now generally available across the developed markets. These cars act as strong competition for imports of new unknown brands: a 5-year-old Civic at $18,000, for example, can hold its own against a new, unproven, and unknown China-branded new car at a similar price. But this barrier does not hold against Chinese EVs, where their lead is just too great.

I know, I know, we must recall that in all these figures Tesla exports from China count as Chinese, even if the firm is American. Tesla does indeed distort our storyline, but as we will see in the Friedel chart, there are numerous "domestic" Chinese OEMs just now joining the party.

Well, they used to be known as the Big Three, and then as the Detroit 3, and now since Stellantis is headquartered in Amsterdam, I don't know what to call them. I'll stick with the D3, since "the Detroit Dutch" doesn't really work well.

I wonder what Cecil Kimber would think of what Morris Garages has become, almost a century later?