First, let’s start with a chart (map) quiz. What does this illustrate?

Last millennium, when I was in B-school (Tuck) we had the good fortune to learn about the nascent field of Systems Dynamics, which was the study of nonlinear (thus often unexpected) behavior of complex systems. In fact, two pioneers in the field, Donnella and Dennis Meadows, were on the Dartmouth faculty. While the Meadows’ focus was on applying SD to the natural world, we were using it to analyze the way corporations worked. (Let’s face it, there are few systems as complex as a car company, especially VW or GM!)

A core case study in the field at the time involved the Kaibab Plateau, which is a geological feature of some thousand square miles bordering the Grand Canyon. The study simplified the Kaibab’s ecosystem down to three interacting populations: wolves, deer, and … shrubbery.1 In summary, the lesson learned ran like this:

In the early 1900s, on the Kaibab Plateau in Arizona, predators such as wolves and mountain lions were systematically removed to protect the local deer population. Initially, this led to a rapid increase in the number of deer, since their natural predators were gone. However, without predators to keep their numbers in check, the deer overgrazed the vegetation, leading to a collapse of the plant ecosystem. Eventually, the deer population crashed as well, due to starvation and disease. This case illustrates a reinforcing feedback loop (deer population growing unchecked) that turns into a balancing loop (ecosystem collapse limiting deer growth), and shows how disrupting one part of an ecological system can lead to unintended and dramatic consequences elsewhere.

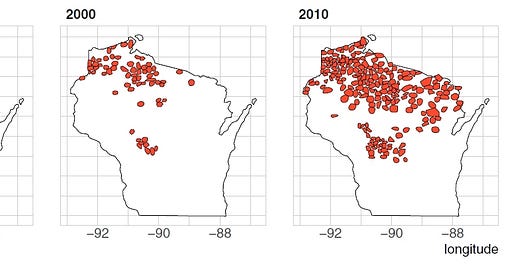

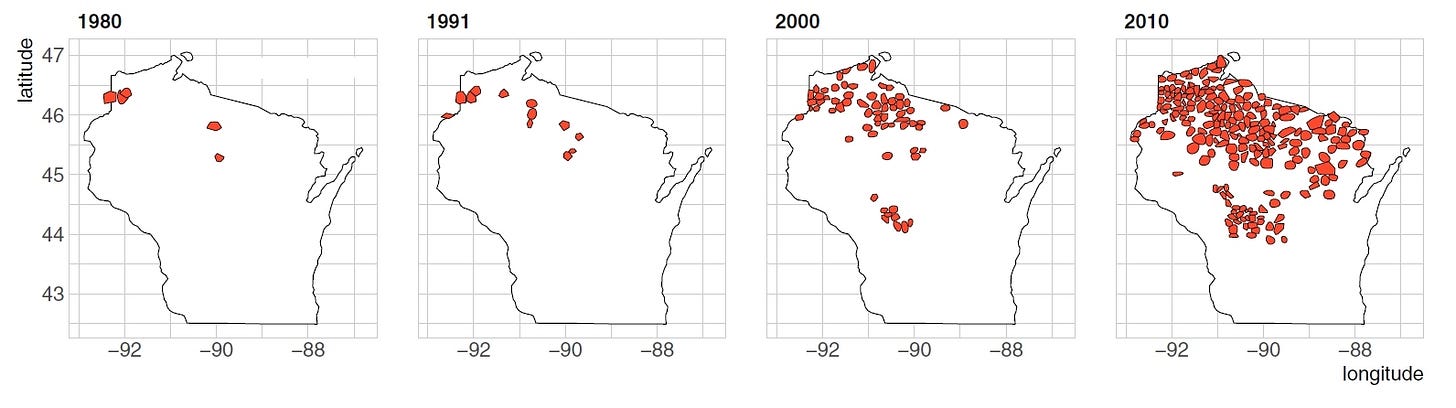

System dynamics in action. Now about that map quiz: at about the same time I was cranking primitive computerized SD models in New Hampshire, over in Wisconsin wolves were starting to repopulate the state. The red dots are wolf packs.

A fact of life (and death) in states like Wisconsin is that of deer-vehicle collisions (DVCs).2 For you city dwellers or inhabitants of southern states, let me inform you that DVCs are indeed a Big Deal. About 1,000,000 occur annually in the USA, resulting in much property damage, a few hundred human deaths, and many thousands of deceased ungulates. (For our European readers, you are likely aware of the problem (notably in Scandinavia) in part because of the infamous Moose Test.)

So now let us bring these strands together: system dynamics, deer, wolves, and cars, as discussed in a great paper, Wolves make roadways safe, by Raynor, Grainger, and Parker3. These three took the opportunity of the natural experiment created by the (re)introduction of wolves into Wisconsin to see how DVCs were, um, impacted: was this a local Kaibab story, where the wolves ate the deer and thus the number of DVCs dropped?4

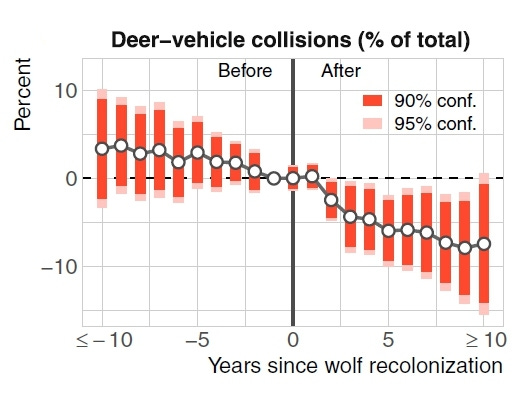

And yes, indeed, this is what happened. Read the paper for all the statistical analysis - and as always, any errors in interpretation are mine, and as always, my thanks to the authors for carrying out this work. Boiling it down (the puns keep multiplying!), here’s a good summary chart:

In sum:

“The preferred model shows that wolf presence reduces DVCs by 23.7% for the average [ Wisconsin ] county, on net.”

That is a lot, and kidding aside, almost certainly means some human lives saved.

But of course the story is not as simple as White Fang dining on Bambi. Of that roughly 24% decline only about 6% is from a reduction in deer population: the rest, about 18%, is from a behavioral shift:

The second channel [ of DVC reduction ] is through changes to deer behavior because wolves create a “landscape of fear” for deer5. Wolves use roads, pipelines, and other linear features as travel corridors, which increases wolves’ travel efficiency and the kill rate of prey near these features…. [ so that ] wolf presence affects deer movement near these features, thereby reducing collision risk for a given number of deer on the landscape.

Who knew? Wolves like roads?!? And thus shoo deer away from highways?

So if wolves proliferate, they eat some deer that might otherwise have leapt in front of your Impala (no, bad choice of car), and induce many more to steer clear of roads in general, for a similar effect.

(The authors point out that this effect provides policymakers with a mechanism for reducing DVCs without necessarily incentivizing hunters to shoot more deer. Maybe the “wolf patrol” is a more humane option than the “hunt and cull.”)

If I have a point here, beyond probably boring you and possibly entertaining you, it is that the integration of the automotive ecosystem into the broader biosphere is broader and deeper than most of us can ever know. Yes, we know about pollution and resource consumption and much more - but then, just when you think you’ve traced back all the impacts, there’s another. I have a few more to share with you in the coming months, so stay tuned if you like this kind of stuff.

PS / update: One reader wrote in and asked if as the result of the wolf population growth there had been some offsetting effect - that is, an increase in vehicle/wolf strikes. As far as I can tell, no. For one thing, government statistics show that about 95% of DVCs are deer, moose, elk, etc. All the rest (excluding just running over something very small), which presumably include wolves, sum to only 5%. I suppose there is a reason we don’t have an idiom in American English along the lines of “Like a wolf in the headlights.” Deer, as I understand it, have poor visual depth perception, and so, especially when temporarily blinded by headlights, have trouble judging the distance and speed of cars, often freezing in (fatal) indecision.

Hang in there, we’ll get to cars!

It’s not every automotive blog that provides teaching moments like this!

In theory I guess they should have looked at the third link in the chain, and studied how many humans starved to death when deprived of venison scraped off the highway. Recall the old Roadkill Cafe joke: “From your grill to ours!” (Possibly apocryphal.) “You know it’s good, it’s straight from the hood!” Okay, I’ll stop now.

Their words, not mine! But way cool, I think.