WFH Revisited, Yet Again

Decoding the H in WFH

As a car industry person I want to know about developments that could affect the demand for cars, positively or negatively. So I try to keep up on the Work From Home (WFH) phenomenon, to see how far WFH might replace the daily commute, which in theory would reduce the demand for cars, at the margin. I’ve nattered on about this several times before, most recently here. (And as always, I advise you turn to the experts for deeper insight and much more data, WFH Research.)

To repeat my own view of the effects of WFH (in the USA) on car demand, in summary: “not much.” That is, taking into account a lot of conflicting research (see my prior post), my net take is that the miles saved by reducing or eliminating the commute are significantly offset by “rebound” miles. (For example, if I used to commute to my Manhattan office, I probably walked down the street to Pret for lunch; but if I remain home in leafy Greenwich instead, I might drive over to the nearest First Watch for lunch. Or if I only have to go into the office two days a week, maybe I will finally buy that remote farmhouse I always craved, and accept as a penalty driving an extra 20 miles twice a week.) Again, the research findings go in various directions, so that a consensus on the net effect has not yet been reached: this is only my own view.

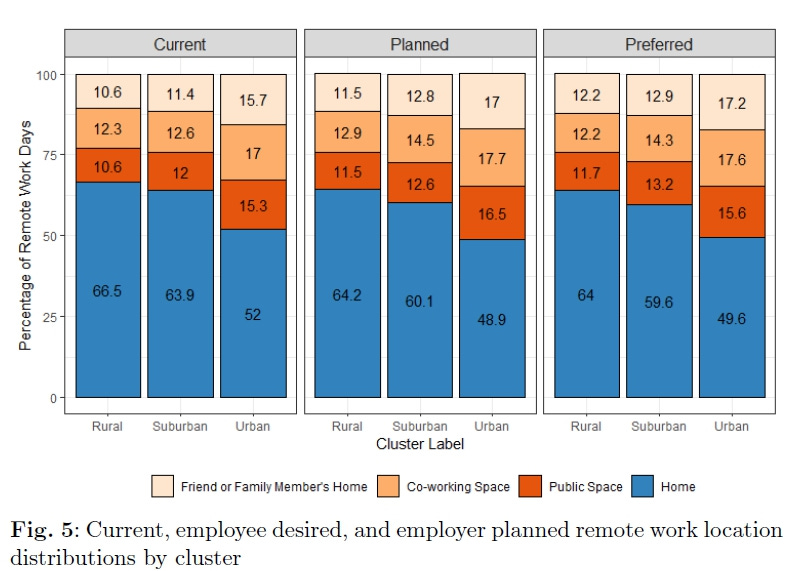

But a recent contribution to the debate comes from here: “The benefi ts and limitations of remote work for reducing carbon emissions,” by Caros, Guo, and Zhao, all at MIT1. Please read the paper for their findings on the titular topic, but my post focuses on one particular chart on one particular sub-topic, which is an analysis of what the “H” in WFH really means. Common sense and personal experience dictate that there is not a binary divide here: work is not either in the office or in the home. People camp out at Starbucks or the local library, for example. And other researchers have delved into this area (see the paper’s literature review). But the Caros et al. paper has a wonderful chart summarizing their findings on this, and this is after all Car Charts, so:

In brief, one can say that about a third of working from home is not actually from simply one’s home, but from someone else’s home, a co-working space, or a public space such as that library or coffee shop. And you can see how the splits vary by rural versus suburban versus urban areas, and also by current actual splits, employer planned, and employee desired working splits2. (It is interesting to me that the employee-preferred mix has a lower amount of work in one’s actual own home than the current level (though the majority of hours remain there): maybe Fido’s incessant pawing at the door for walkies is getting to us.) And were you as surprised as I was about how much is done at someone else’s home? (“Hey, Mom, is it okay to work at your house? No, I won’t eat all the food in the fridge like I did last time…”)

In any case, the so-what is what you might expect: patterns like these erode the simplistic assumption that ditching the 10-mile commute saves 10 miles. It does not: it’s more like 7? That’s still real miles saved and real emissions reduced and real time stuck in traffic cut - but it is not a 100% reduction across the board. As the authors write (and their focus is on emissions, not miles or numbers of cars, though all three variables tend to move roughly together):

“… in the United States, remote workers are choosing to spend approximately one third of their remote work hours outside of the home at cafe’s, co-working spaces or the homes of friends and family. Commutes to these “third places" could offset much of the reduction in congestion and carbon emissions from commuting that could be expected from greater shares of remote work. … [ Our ] study reveals that ignoring third places leads to an underestimation of carbon emissions from commute-based travel demand by 470 gigatons per year, or 24% of the total true emissions.”

My gut feel is the impact of WFH in the USA in terms of numbers of cars in driveways will be pretty close to zero. Just picking numbers out of the air, I might drive my car 9,000 miles a year instead of 15,000, thanks to WFH, but that 9,000 is still too high to ditch the car entirely, in favor of Lyft or Waymo or a bike. But since cars age more by miles than years, I might own that car 7 years now instead of 6, and so that could hit car sales. (I invite readers to create their own systems dynamics model of all the factors involved: I tried it once and all I can say is one rabbit hole led to another.3) We’ll see. The picture remains murky.

But I think it might be time to change the abbreviation: WFH (work from home) is not really accurate. What do you think of WNH (work near home)?

To which I was referred from here: “The effect of remote work on urban transportation emissions: evidence from 141 cities,” by Shen, Wang, Caros, and Zhao, again all at MIT.

These are splits of the WFH days, not of total days worked. So not shown here is the split between WFH and work-in-the-office. Note that the authors use “preferred” and “desired” interchangeably, in discussing what employees would like. “Planned” always refers to employer wants. Not sure why the employer is concerned about where the WFH hours are spent (versus their total number).

E.g., if I sold the car it leaves the household fleet, right? But what if I sold it to my daughter, so it’s still in the driveway?