On July 13, 2023, I wrote a post titled “Tesla's other great achievement,” with the subtitle “Is the radical simplicity of its products sustainable?” My point with that post was to highlight Tesla’s incredible feat of leveraging its four models (two of which, S and X, were essentially niche products even then) into about 1,300,000 units sold (in 2022). I contrasted this achievement with Mercedes’s selling some 700,000 more units (about 2 million in total), but requiring about four dozen models to do so (not counting a lot of AMG variants)! The benefits to Tesla of pulling this off are numerous, and I listed a few (lower production cost, lower cost of aftersales support, enablement of a streamlined sales channel, etc.).

After praising on the Californian Texan OEM, I did sound a cautionary note:

There is only one problem, and that is the pesky, annoying, customer. … Supply loves simplification, but demand can set limits to it. The question is, will consumers, accustomed to the multiple dimensions of choice they have enjoyed for a century or so, accept simplicity? The easy, short-term answer is “Yes, of course.” Tesla proves this. The Tesla Y was by some measures the best-selling car in the world in the first quarter of this year (leaving aside definitional issues about pickup trucks and cross-overs). Seems like a win for simplicity, at least to me! But this answer leads to another question, which we have heard asked about Tesla repeatedly, in various fields: is this concept a role model or an exception? Every OEM CEO has to make this call, because if the former is true, that customers prefer or at least do not object to having less choice, then we are going to see product line and options pruning on a Biblical scale. But if the latter is true, and customers want to spec their car to the extent they now spec their Starbucks order, traditional OEMs should stay their variety-burdened course.

And in my view the harder, long-term answer is “Maybe not.” We may already be at “peak simplicity.”

(And I cited leading Tesla analyst Toni Sacconaghi (at BernsteinSG) in support of this mildly skeptical view.1)

Why do I bring this up now? Two reasons.

First, the simplicity chickens have indeed come home to roost2 Not only has Tesla’s market share (in the US) fallen, but also its unit sales. And this is despite massive (on the order of 25%) price cuts, the launching of some advertising, increasing amounts of cars sold directly from inventory (versus building to order), use of leasing subvention, and all the other promotional stuff that Regular Car Companies That Do Not Have a Dojo Brain or an Optimus Robot employ. It looks like, indeed, Americans have begun to tire of buying the same-old-same-old Models 3 and Y (not to mention S and X, of course).3

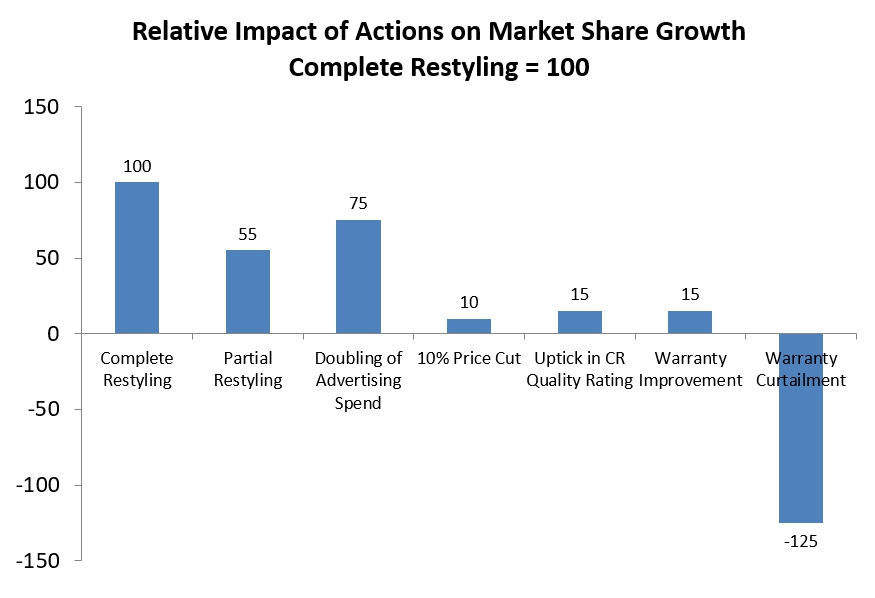

Second, this development lets me showcase one of my favorite Car Charts, drawn from one of the best academic papers on the American car market ever written: Non-price determinants of automotive demand: Restyling matters most, by Korenok, Millner, and Hoffer. (To continue with the superlatives, George E. Hoffer, of Virginia Commonwealth University, is one of the greatest students of the demand for automobiles whom I have ever met4.) Here it is:

Source: Korenok, Miller, Hoffer

Okay, let’s interpret this. The authors looked at sales (expressed as market share growth, to remove scale distortions), in the USA, of some 150 vehicle “lines” or models, over the course of a decade, and regressed those sales against a number of variables, including prices, OEM advertising spend, Consumer Reports quality ratings, changes to the manufacturer’s warranty duration, and crucially, restyling of the exterior (bodywork). To quantify the restyling variable, the authors painstakingly reviewed images of every vehicle line in every year and assigned to each a rating of No restyling, Partial restyling, or Complete restyling.5

It is clear from the chart that, short of a warranty curtailment (it is a very negative signal to the market if an OEM reduces the number of years a car is warrantied), the newness of a car’s looks is paramount. To quote the paper:

The positive impact of a restyling dominates the other demand determinants … A complete restyling on average has a ten times greater impact on market share growth rate than even a 10% reduction in relative price. Manufacturers would have to double relative advertising expenditures to achieve an effect comparable to a complete restyling.

And crucially, note that nowhere in this research is the quality of the restyling examined. The authors, for example, do not distinguish between restylings that Car and Driver panned, and facelifts that Road & Track fell in love with. At some level, for American buyers at least, it just doesn’t matter. When it comes to the advertising tag line “New and Improved!” we really want new… and improved is just a bonus6.

For a few years now we wondered if this preference had changed. Maybe just updating the software every few months was enough. Maybe owning one of a horde of nearly-identical 3s and Ys was cool. But the recent erosion in Tesla’s fortunes seem to indicate no: the American consumer really does have a lust for the novel: we really want the shiny new thing7. Tesla is trying hard to maintain its leadership position, but with just two very similar main models, one introduced in 2017 and the other in 2020, with no significant styling changes since, while the competition launches new or refreshed products almost weekly. Continued growth with just two (aging) models now seems unlikely - though it did work in the past.

Simplicity, perhaps, has peaked8.

From Toni: “Tesla’s volume ambitions represented massive outliers versus what was historically achievable. Given the competitive nature of the global auto market, dominant luxury cars ($45,000+) have historically topped out at 400 - 500,000 global sales per year, while the highest volume mass market ($25K- $35,000) cars and SUVs have topped out at 800,000 – 1,000,000 units per year, translating to ~10% segment share for mass market sedans and ~7% for mass market SUVs. Tesla’s volume goals were for Model 3 + Model Y to be 3 - 4,000,000 units, which represent nearly 50% of global market share in their categories. Notably, the Model 3 and Model Y have already achieved outlier volumes within their price segment, and were the #1 and #2 best selling luxury cars in 2022 - and yet they would still need to grow annual volumes by three times to achieve Tesla's volume goals. … We also note that in EVs, incremental volumes are typically captured by new models, which provides further reasons for caution about Tesla's ability to continue to grow Model 3 and Model Y beyond already impressive levels today.” From “Why isn't Tesla seeing more price elasticity?”, April 25, 2023.

This is the worst metaphor I have ever used. I am kind of proud of it. It’s all uphill from here.

Of course, there are other factors involved, but to protect my sanity I am not going to get into the World of Musk and the Politics of EVs and the CyberCamino, and all that.

George also early on saw the potential for CarMax, when most other analysts were doubtful.

Definitions as used in the paper, of each level of restyling, edited: “Partial restyling [ was coded ] if models underwent grill, tail lamp lens, trim, front/rear fascia, and/or partial sheet metal changes. Complete restyling [ was coded ] if vehicles underwent restyling with at least all new sheet metal and “greenhouses.” Also, new entrants were given a value of complete restyling. Since this paper focuses on the impact of styling changes on consumer markets, we did not distinguish between restyling on existing versus new platforms (chassis) [ which are mostly invisible to consumers ].”

For a purely hypothetical example, you know thousands if not millions of people will line up for the iPhone 16, even if in the fine print of the product specs it turned out not much had actually changed. It’s just the new model!

And to be fair, if nothing else, Cybertruck does qualify as the King of All Restylings!

As always, however, history raises its grizzled head. We cannot say that a very simple product line is a new concept, from Tesla or any other contemporary OEM. From the paper, a reminder: “Between 1956 and 1959, Chevrolet had one model-line (excluding on average 7,000 Corvettes annually), the standard Chevrolet, producing approximately 1.4 million units annually.” That would change of course, and also of course the story is more complex than the raw numbers indicate. Read the paper!